Reģistrējieties, lai lasītu žurnāla digitālo versiju, kā arī redzētu savu abonēšanas periodu un ērti abonētu Rīgas Laiku tiešsaistē.

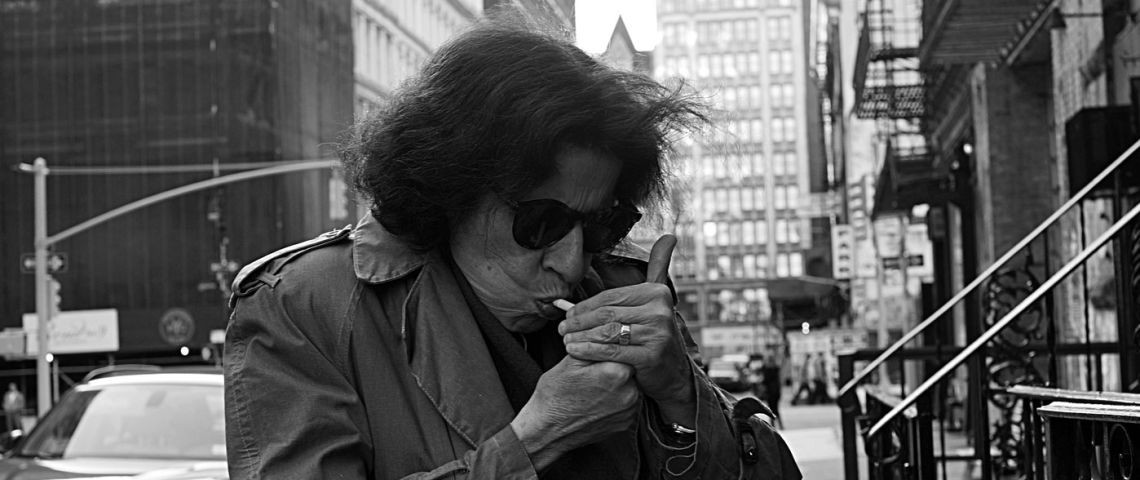

Through an accident of birth, Socrates and Fran Lebowitz never actually met, which is sad, because they would have enjoyed each other enormously. The two of them practice a similar type of rationality and share a passionate commitment to applying it to any and all subject matter. Perhaps wit, at least in the case of Socrates and Fran, consists at least partly in using reason when others would use superstition, prejudice, or impulses of the id. The way they do this is so unusual that we find it amazing and respond by laughing.

Fran is belligerent in insisting that she is speaking from her own position on the planet, telling us about what she personally likes and the world she personally would like to see around her—and yet somehow her disappointed hopes have an extraordinary universality. She is a born aesthete and intellectual with a radical belief in human equality and a radical contempt for the power of money. She loves the pleasures of the world, but she happens to be one of the few people one can name who has repeatedly rejected the opportunity to use her talents and her charisma to make enormous sums of cash.

It seems presumptuous and possibly absurd in the abstract to imagine that the United States or New York City in particular still have something special to offer the world, so I’ll restrict myself to saying that in this great interview we can clearly see that Fran Lebowitz’s words and her rage and her wonderful use of the English language remain undimmed.

Wallace Shawn

On the bus from Boston I was browsing through a book called A Journey into Dorothy Parker's New York. Tell me about your New York.

Here’s the thing about New York: every person’s New York disappears. I didn’t realize that when I was a child reading Dorothy Parker and those writers of the Algonquin Round Table of the 1920s. When I was young, people who wanted to come to New York—who had read about it, seen movies about it—they didn’t realize it either never existed like in the movies or it would be gone by the time they got there. So I didn’t know when I was a teenager in the 1960s that Dorothy Parker’s New York had been gone for 40 years already. I came to New York when I was 18, and the city changes so much that the New York of my youth is completely gone too. The New York I inhabit now is the New York everybody else inhabits, but with bitter memory. I always tell friends my age, “When you say New York used to be better you have to be careful about what you mean. Was it better to be 20 or was it better here in 1970?” I believe both things are true, but there’s a difference.

What was better about New York in 1970? About you it’s clear: you were young.

Yes, I was 20, and it’s more fun to be 20 than 60—everyone knows that. Well, most people think New York was worse then because it was in bad financial condition and there was a lot of crime, so people always say, “Oh, did you like it better when it was dangerous and dirty?” And I say, “No, of course, not.” But these things aren’t connected; they just happen to be connected in people’s minds. There wasn’t the kind of media there is now. There was no New York Magazine—imagine. New York Magazine, in my opinion, is one of the first things that ruined my New York. Before them there was no magazine or newspaper devoted to saying, “These people eat here; these people go to this bar; these people live here.” You had to know people; you had to live here; you had to have a real familiarity with the city. They started to write about these things, and then the tourists would come, and before long it would disappear. So I blame New York Magazine, and I blame most of the people now lauded for having saved New York from bankruptcy. Everybody keeps saying,“In the 1970s New York was going bankrupt.” Well, it was, but I didn’t notice because I was young and poor. You know, people with no money don’t notice the economy. The economy is for people who have money; it doesn’t exist for people who have no money. I didn’t have any money, and I didn’t know if times were good or bad; it didn’t make any difference to me. People say, “Oh, New York was so cheap then!” But it wasn’t. It was always more expensive than it should be. Of course, it was cheaper than it is now but… I used to live in a one-room apartment in the West Village; it was 121 dollars and 78 cents a month and very expensive for the time. But there were lots of jobs. I drove a taxi, I was a cleaning lady; you could always get —

You were a taxi driver?!

Yes, I was. It’s a horrible job. I was always able to get a bad job. There were a million bad jobs, so I could always work and make enough money. I also had this idea of enough money—like enough money was enough money. I paid my rent; I could eat; I could buy cigarettes—30 cents a pack, not 15 dollars. There wasn’t this preoccupation with money among young people like there is now. To me it seems totally crazy for people who are young.

Still I don’t get from your story what was better about New York when you were young.

It was freer; there was a lot of freedom. I could lead a life I liked which was very lazy. Mostly I didn’t work. Mostly I hung around with my friends. I worked just enough to pay my rent, my food, and I hung around. The thing that’s important to being young and being an artist is to hang around. There wasn’t this big work ethic there is now. Everybody was like hanging around. So it was freer and… I don’t know how much you’ve been here, but there are these cameras all around us, which I hate. There are more cops, more people looking at you all the time… and not just after September 11th, but even before that. It’s a suburban attitude; it’s not urban. To control your physical environment all the time is not an urban idea. The urban idea should be freer. It’s not as free.

For you freedom means doing whatever you want?

That’s right, freedom to do whatever you want. I’m not saying murdering people or robbing people, but doing whatever you want without having people tell you,“You can do this here; you can’t do this here; you can’t walk here.” Take the parks, for instance. The parks are partly privatized now, all the parks.

By whom?

By Bloomberg, the mayor. To me, Bloomberg is the major villain of New York. Central Park is run by the Central Park Conservancy—it sounds very nice; it sounds like a public institution, but it’s not. It’s private money. And as soon as you have private money in a public place, the private money controls it.

In what way does it control Central Park?

They put fences around the grass and signs: Don’t walk on the grass. It’s a park! A park means ‘Walk on the grass’, I think. You read ‘Don’t walk on the grass’ only on suburban lawns. And then they close the parks at midnight. They never closed parks before.

In my town, in Riga, smoking is forbidden in parks.

Now it is here too. That’s recent; that happened maybe two years ago.

I was in New York when the smoking ban went into effect for restaurants. What damage has the ban done to social life?

Tremendous. Tremendous. As soon as he [Bloomberg] passed that [ban], I saw him somewhere and I said, “Do you know what it’s called—sitting around in bars, smoking and drinking and talking?” He said, “What?” I said, “They call it the history of art. That’s what it’s called.” Everyone thinks I say this because I smoke and that’s what I do. But truthfully I believe that. I’d believe that if I didn’t smoke. It’s also very interesting that someone as rich as Michael Bloomberg… You know, rich people and Republicans are always fighting for private property rights. This restaurant is private property; it’s not owned by the state. If someone buys a restaurant and people want to smoke there, they should be allowed to smoke there. If you don’t want to be around people who smoke, don’t come in. That’s what I think.

But could you identify the damage it’s done?

The damage… First of all, it enables a tremendous level of smugness. Americans are only allowed to express hatred for one thing now, and that’s cigarette smokers. Even though people have tons of prejudices, they’re not allowed to express them. But you are allowed to say you hate cigarette smokers. Here’s what it means to me: anti-smoking sentiment has replaced the anti-homosexual thing. They’ve switched places. When I was young, it was actually illegal to be homosexual. You had to pretend to be straight to find a job, for sure. And they always said what was dangerous about homosexuals was that they’d convince kids to be homosexual. It was this second-hand homosexuality they were afraid of. And there was tremendous contempt expressed for homosexuals that was totally allowed, totally encouraged. You can’t do that anymore. People still hate homosexuals, but they can’t say that. Now they’re allowed to say it about people who smoke. People yell at you in the street the way they used to yell at homosexuals in the street. So to me, they’ve switched places. The only difference is you can hide that you’re gay, but you can’t hide smoking. I think it has a tremendous effect. I also don’t believe second-hand smoke is dangerous.

There are plenty of medical studies…

Ask any doctor or scientist you know, “Is it really dangerous to sit in a restaurant where someone smokes? ” The honest ones will say, “No, it’s not.” How could it be? I mean, look, I’m 62 years old; I know people who have died from any possible cause you can imagine. And I know many people who died from smoking. But I don’t know anyone who died from someone else’s smoking.

Back to the connection between art history and smoking… There have been long periods, centuries, when art was made without a single cigarette. Where do you see the connection?

I see the connection in a certain kind of urban life. In the modern era, starting from the 18th century, there’s a kind of coffee-house life. You know: a life of hanging around, talking to people; it could be in a bar, it could be in a coffee house. Even before cigarettes were invented—here at least—there was pipe smoking. There’s still a restaurant here from Abraham Lincoln’s time. Men who went to this restaurant had pipes with their names on them; the pipes are still there. It’s part of relaxation. Nicotine is a stimulant and part of that life; it certainly was for people of my era.

A couple of days ago I was talking with Jonas Mekas. He was part of New York’s creative scene in the 1960s and ’70s.

And the 1950s. He’s older than me.

Yes, he’s 90 now.

Is that old? What do you think is old?

I think my perception of what’s old changes as I age.

For me too, but still I acknowledge that 90 is old, come on.

I asked him where the tremendous creative energy of that period in New York went. And he said it spread, that it’s all over the place now. I’m not sure I buy this picture. What do you think? Where did all the creative energy go?

I really don’t know much about it. Everyone knows that in certain areas, certain countries or cities, you have this efflorescence of creativity. You have the Renaissance in Italy, different moments like this. There are always reasons but it also requires… It wasn’t just the Medici who made the Renaissance. It was also the unbelievable cosmic luck of having all these geniuses alive at the same time. One thing I do believe is random is genius. Genius is totally random. It can’t be encouraged. Of course, environment is an influence… If Albert Einstein had been born in say 1015, he would not have been able to think about what he thought, even with the same brain. And the 1950s and 1960s were a very particular time in New York. I was a child then, so I wasn’t part of that.

You were part of the 1970s.

The 1970s, yes. I think one of the things required is density of population. That’s why it happens in cities and not in rural areas. When I was young, I was out all the time—because I lived in a horrible place. Everyone I knew lived in some horrible place. Who wanted to stay in these horrible apartments? No one. So we were out all the time. And being out all the time you’re with lots of people who are talented or interesting, or whatever. And then you get a certain expression of that. You certainly have that in Dorothy Parker’s era. That was a very verbal era. It was an era where verbal ability and writing ability were very much admired generally.

But you’ve said the same about the ’70s in New York—that verbal ability was still admired.

Yes, but just by a few people. In the 1920s it was admired by the whole country. Dorothy Parker and all these people [of the Algonquin Round Table] were famous because of a newspaper column written by a man named Franklin Pierce Adams. He was friends with these people and he wrote about them. He wrote what they said when they were hanging around together, and people all over the country read these stories. It raised the status of writing. When I was young, people said it was much better to be a writer in the 1920s and 1930s because “look at how people admired that and now they don’t.” That was in the 1970s. And the ’70s were certainly the beginning of the end in a way, because that’s when the image really started to take over. Now it has completely won.

The image over the word, you mean?

Yes. In America I’ve always seen it as a contest between LA and New York. LA was the place of the image, and New York the place of the word. There can’t be a single sane person today who doesn’t know that LA has won. Naturally the image carries more weight because everyone can apprehend it. It doesn’t matter what language you speak. Take this magazine: I can’t read it, but I can look at the pictures. And I’ll be able to look at the pictures in any magazine in any language. Now, I happen to be a person who is very frustrated that I can’t read this because I want to read it. But many people don’t. They don’t care.

You described the 1920s and earlier as a period when writers were at the centre of culture. What’s at the centre of culture now?

Money. Money and nothing else. Money has obliterated everything. There are no competing values to money.… Money, I am sorry to say. Money has replaced everything else!

But money is just a means of —

To us, OK? But if you’re asking what moves this culture, it’s money. Nothing else. If they say otherwise, they lie. There are people who care about certain things, people who write books and things like that, but they have no power in the culture. None. That’s why you have Michael Bloomberg as mayor. You know what people say they like about him? That he’s the richest man in New York. To me this should disqualify someone from being a mayor. You cannot be the mayor if you’re the richest man. But people admire him. I mean, more than admire. Americans have always loved a buck, but they used to have other values as well. There used to be things that competed with that. People used to pretend to have read certain books because it carried a kind of status. Now they don’t even pretend because it doesn’t matter.

Aren’t you simplifying the picture?

Yes, that’s my profession. I mean, when I was young I realized that some of my friends had money, their families were rich. They never talked about it. Not because they were so modest but because it wasn’t fashionable for young people to care about money. Today people ask you all the time, “How much did your apartment cost? How much is your rent? How much…?” It’s become perfectly acceptable, especially among young people. Young people think about money and about what they’re going do when they’re old. To me that’s very odd. No one thought about that when I was young.

You’re referring to social life in general now. Do any aspects of cultural life confirm this?

For instance, the visual arts—painters and sculptors… It used to be called “the art world” in New York; now it’s called “the market”. It’s called the market by artists; it’s called the market by museums and galleries; and by the way, museums, galleries and auction houses—they’re all one thing. The Museum of Modern Art is a perfect example. I grew up in New Jersey, and when we came to New York, I would beg [my parents] to go to the Museum of Modern Art, which was in the original building then. It was like a religious institution in the sense that it was the temple of art. And there were never a million people there; it was quiet and people were looking at the art. There wasn’t this idea that the purpose of museums is to lure in millions of people. The idea was: if you care, here it is. And if you don’t, don’t come in. Now if you talk to museum directors, all they talk about is how many people attended this or that show. You walk into any museum and the first thing you smell is food. There’s a restaurant because what people really want is a restaurant. You go to the Met, which literally was a temple, and at the end of the gallery you can buy a T-shirt or a cup with Francis Bacon… And then they tell you,“A million people came to see this show.” There aren’t a million people who care about art! These people who are coming—they don’t have to come to the museum. They talk, they bring babies. Babies! In strollers, babies, two-year-olds—what are they doing in the museum? They shouldn’t be there! Some say the parents are trying to show their children art. They’re not. They just bring them everywhere and make it unbearable for people who want to look at the paintings.

Do you still consider babies to be talking animals? You’ve called them talking animals.

I have? I don’t remember… By the way, I like children, just not at the Met. If I go to your house and you have children, I’m delighted to see them. If I invite you to my house and I invite your children, I’m delighted to see them. If I’m in a restaurant having dinner at 9.30, I don’t want to see them—because if there’s just one child in a restaurant, the entire restaurant devolves to that child’s level. I don’t think the purpose of museums should be to see how many people who don’t care about art visit the museum. Having lines around the block to a museum doesn’t suddenly mean I live in a country where people are devoted to art. It doesn’t mean that. Some ten years ago the Guggenheim had a show of motorcycles. Motorcycles! After the opening I went to a party somewhere and I vented my anger. A girl who was there said, “You know, Fran, you’re wrong; people love motorcycles.” And I said, “Yes, but that doesn’t mean they belong in the Guggenheim.” You know what people like more? Free beer. Put up a big sign saying ‘Free Beer’ and you’ll have millions of people at the Guggenheim. But that’s not what the Guggenheim is for. It’s like I used to say to my publisher, “People don’t like books; they like chocolate. Why don’t we put a chocolate bar in every book, and then they’ll buy the book.” More people like chocolate bars than books. That doesn’t mean you have to make books like chocolate bars.

Edible books?

Yes, edible books. Do you know the guy who owns the Strand Bookstore?

I’m familiar with the bookstore but not with the guy.

OK, the guy who owns the Strand Bookstore put candy bars at the front counter where you pay for books. And everybody said, “Fred, why did you put the candy bars there?” And he goes, “I sell more candy bars than books.” And I say, “Fred, but this is a bookstore.”

If you could make an edible book …

People would like that.

And where do you see the problem with edible books?

I wouldn’t have a problem. My library just wouldn’t be filled with them. It’s not that I’m astonished most people don’t like books or most people don’t care about art. That doesn’t bother me. What I care about is that places with these things shouldn’t be trying to get most people to come to them. In other words, there’s no reason for a museum to compete with a football stadium.

Is there any contemporary whose opinion interests you?

Yes, I have friends whose opinion interests me. But my lack of interest in other people is not confined to my contemporaries.

You’re not interested in people who are long dead.

Well, it depends. I wouldn’t make that kind of blanket statement.

That was an attempt at provocation.

I don’t need to be provoked. As you can see, I’m in a constant state of rage.

Against what?

Pretty much my fellow men.

Do you love them?

Only in the abstract. Not individually. I would defend the rights of my fellow men, but personally I’d like them to sort of keep their distance.

All of them?

No, not all of them. But in the aggregate—yes. I respect the rights and humanity of my fellow men, but I’d rather you didn’t sit right next to me in the subway.

When Martin Scorsese made the documentary about you, he made your image, your voice, available to many people.

Doesn’t that contradict you not wanting to get involved with them?

No, I’m not there when they’re watching that movie.

But what interest could you have in spreading your image?

I want people to listen to me. I mean that in the most dictatorial sense. I want people to do what I say. They never have and I have no expectation they ever will. It’s not that I don’t want people to know what I think. I just don’t want them to sit right next to me.

But why do you want them to do what you want?

Because I’m right.

How do you know that?

I was just born that way.

You mean, when you were a talking animal, two years old, you were already right?

Well, I don’t know. I was apparently a fairly emphatic child. On the other hand, I was a child when children weren’t allowed to have opinions. I was born in 1950, and in the 1950s in this country it really didn’t matter what kind of family you came from. No one asked you anything. No parents, no teachers, no grandparents ever asked you anything. They told you what to do. It was like one long lesson.

And you’d like to continue along the same line?

Well, I don’t have any children, so I like to tell other people what to do. The bad thing is that when I was a child, I imagined I’d become a grown-up and everybody would listen to me. But just when you’re grown up, it switches. All of a sudden the entire society decides to switch its idea of how to behave to children.

Name a couple of people whose opinion interests you, apart from yourself.

Toni Morrison. I just lunched with her today, before I met you. Toni has something that very few people have—she has wisdom, not just opinions. Everybody has opinions. But Toni knows things; she really does. I’ve known her since 1978 and I always seek her advice. Toni has ideas and I’m interested in ideas, and I’m interested in her opinions too. She’s from my parents’ generation but she’s a good example and not just for me. Everybody should listen to her.

And who else?

I knew you would ask that, and I knew I would have a hard time thinking of… a second person. (Thinking.) I’m sure there are other people, but no one comes to mind.

One of the funniest stories you tell in Martin Scorsese’s documentary is the one in which Toni Morrison is being given the Nobel Prize, and you’re seated at the children’s table at the Nobel Prize ceremony. Is it true?

Everything I say is true. It’s true but it was the Nobel Prize ball, not the ceremony. We were there for five days, and this was the last final thing of many events. The Nobel Prize ball is in fact a ball—it’s white tie for men—and the invitation says ‘full decorations’, meaning men who have medals are to wear them, which they do. It’s very formal and very long, like six hours, maybe a little less. It’s in the old city hall; it’s Christmas, and in every window they have candles for Christmas, torches in the streets; it’s incredibly beautiful. And the entire city of Stockholm seemed to be standing in the streets applauding the laureates. That would never happen here. And the seating is very formal. When you come in, there’s this thing where you take your seat with your table number or something like that. Toni brought a lot of friends with her, maybe eight or ten friends, so I walk in with all these people and everyone is at the same table but me.

Why?

I don’t know. So I go in, to my table, and seven or eight Swedish aristocrats are already sitting there. The women have tiaras, the men have military things; they’re very erect. And they glare at me, and the one thing you could tell from their look was We don’t know who she is, but she is not a Swedish aristocrat. What is she doing at this table? And I’m thinking Who are these people? And one of them complained to someone.

About your presence at their table?

Yes. So I show them my thing, “I’m not like crashing your table, this is my… sorry.” And there was a woman I recognized. The Nobel committee assigns a person to every laureate, someone in charge of them. So I’d met this woman before with Toni. And I said to her, “There’s been some kind of mistake in the seating.” And they’re very nice, the Swedish people, but she was very insulted. This had never happened and it was not a possibility. She went to another woman whose actual full-time profession was seating for this ball. She had never made a mistake; no mistake had ever been made in the history of the Nobel Prize since 1902. So finally it turned out there was a mistake, but now there was no room for me. Because everything is exactly… it’s very precise. And here’s the other thing: the importance of where you sit has to do with how close you are to the king. All the friends I was with were pretty far from the king. The Swedish aristocrats were closer. But the children were really close to the king. So they bring me to this table, and I look at it and there’s like a bunch of children. Children! I don’t even mean teenagers. Children! So I sit at the table with a bunch of children, and I don’t understand what I’m doing there. Even if they were cute, some of the children, they’re not people you want to sit with at a formal dinner. Luckily you could still smoke then at the Nobel Prize ball; otherwise I would have gone out of my mind.

You could smoke there? at the table? with children?

Yes. This smoking thing still existed. Toni won the Nobel Prize in ’92 or ’93, and you could smoke in the elevators in Stockholm. The elevator was full of smoke; I thought it was on fire. And then I look—there’s this guy smoking a pipe.

So you don’t have especially fond memories of the Nobel Prize ball.

Oh, no, I do have fond memories. Because even though I had to sit with all these children, it was a very beautiful event. And I was so happy for Toni, that she won the prize.

You didn’t feel envy?

No, not envy. I don’t really compare myself to other people. If someone I hated won the Nobel Prize, I would perhaps be annoyed. But I wouldn’t feel envy because envy to me… Often people express envy for things, like, “I wish I had my own plane.” And I would say, “If you give me a plane, I’m happy. If you say I have to be and live the life of a person who can afford a plane—no, thanks.”

Have you wasted a lot of time in your life?

Yes. I believe myself to be the eminent timewaster of my generation.

How have you wasted your time?

I would say I’ve wasted most of my time talking and reading.

Why would you consider reading a waste of time?

Because I’ve mostly read when I should have been writing. I’ve almost never spent time reading without feeling guilty, and because I was always—even from a young age—yelled at for reading so much. When I was a child, I read instead of doing my schoolwork. My mother would say, “I know you’re reading in there!” First I was supposed to be doing my homework. So I mostly feel guilty when I’m reading.

You still do?

Yes, still. Because now when I’m reading, I’m not doing my homework, I’m not working.

You said that talking is the other way you waste time. Isn’t talking, having a decent conversation, the most enjoyable thing in life? Why would you call it a waste of time?

Well, if I worked more, I wouldn’t consider talking a waste of time. But if you feel that you haven’t done the work you’re supposed to be doing, then everything that isn’t writing seems like a waste of time.

Couldn’t you become a talk show host and invite the most interesting people in the country to talk with you?

I’ve turned this down many times. People who are on television all the time… I would never want to be that well known, that famous. It’s a level of fame that seems unbearable to me. People on TV are recognised by everybody. I never wanted to be recognised by everybody. It’s very invasive. If you know people on television, you can’t be with them for one minute. Everybody talks to them. Everybody. I used to have a friend who was on TV every day; I was walking with him once on 57th street, and a bus driver stopped the bus and jumped off to talk to him. That would be unbearable. So, that’s one reason. And another reason is—people who are TV talk show hosts ask questions; they don’t answer them.

But still, imagine you were a host. Who would be the first three people you’d invite on your show?

I couldn’t think of three people, which is why I wouldn’t want to do it.

I understand you’ve never been married. Why?

Well, I’m gay, first of all.

That doesn’t mean…

Well, it used to, of course it did.

But now people get…

No, I wouldn’t, not me. First of all, I don’t like domestic life. I’ve lived alone my whole life since I was 18. I didn’t even want to share my apartment with a friend. I don’t like that way of life; I’m very bad at it by the way—because I’m not a monogamous person by nature, and I don’t pretend to be one. To me that kind of intimacy seems quickly dull, really boring. And I don’t want the responsibility. That’s why when I heard gay marriage being talked about, at first it sounded like a joke to me. Because when it was very hard to be gay there were two upsides, even when you risked jail. One was you didn’t have to go to the army, and the other was you didn’t have to get married. Those were the two most confining institutions in the country. I don’t care that people want to get married, but it will never be me. Ever.

For decades, almost a century, certain women have been fighting for equality with men. Are women equal to men?

You mean: Are they treated equally, or intrinsically equal?

Are they intrinsically equal?

Of course they are. Are they treated equally? No. Women are paid less than men in almost every single profession. There’s never been a woman president. The number of women in Congress is very small. There’s never been a woman mayor of New York. There’s never been… And there’s a reason for this.

Because women aren’t as clever as men?

Yeah, that’s the reason. (Sneers.) The reason is… as a friend of mine says, men own the world and human beings never give up something they own. So there’s the entrenched power of men for centuries but there’s also something else. There really are differences between men and women, biological differences. My belief is that men are physically stronger than women. Obviously in an environment where physical strength predicts survival, men will be in charge. If it’s only men who can fight lions or whatever existed then, men will be in charge. And that’s ended because now we don’t live in an environment where physical strength has any importance at all. But we’ll always live in an environment where women have babies. The fact that women have babies is the problem—the fact that they’re able to have babies, but, more importantly, that they want to have babies. And that’s real.

But why is it a problem?

First of all, it takes a tremendous amount of time to raise children.

And that’s a problem in what sense?

It’s a problem if you want to pay most of your attention to something else. Once a woman has a baby, her attention is never not diverted. A woman’s focus shifts the second she has a baby. It’s biological. That’s why babies stay alive. If babies’ survival depended on how much men paid attention to them, there would be no second generation. Baby’s survival depends on the fact that woman and baby are very close. This is my observation of other people, because it’s never happened to me. I see their focus shift. Then also women have to deal with the fact that men don’t want to give up this power, and men take men more seriously than they take women. That is just a fact. You would never know that because you are not a woman.

I know that.

Certain kinds of men will not pay attention to you at all—in other words: the less educated men are, the less they’ll pay attention to you. For instance, I take my car through a car wash, and the car wash machine breaks something on my car. So I show the man running the car wash and say, “Look, this thing was broken, the antenna or whatever.” And he goes, “It can’t be like that; it wasn’t broken.” And he just looks away, pays no attention to me.

And do you think he ignores you because you’re a woman?

I know he does. Luckily for me, I have a friend living in the next building. It’s like 11.30 at night. I get my friend to come downstairs. My friend, who is a man, comes downstairs, and he says to this guy, “This is my friend and you broke her car.” And then the guy goes, “Oh, yeah, you‘re right, sorry; how much is it?” And he gives me money.

Maybe it’s not because you’re a woman; maybe you didn’t look serious enough.

Here is what I don’t look enough: male! OK? Every woman who lives in New York will tell you that for certain things you have to get a male to talk to these people. They don’t even respond to you; they just walk away.

How do you understand gays wanting to adopt children?

I don’t understand it. Here’s my theory about this. When the AIDS epidemic started, it was a terrifying, terrorizing period because at first no one knew what it was. At first they thought it was from poppers, which is a kind of drug. It didn’t occur to anyone it could be from sex. Because people of my age always thought Sex is good for you. It’s a healthy thing, like orange juice. We thought the same about drugs at the beginning. When people started dying from AIDS, people of my age, when they finally started knowing where it came from, they were terrified. People died in like five minutes. And it was a very grotesque death, something from the Middle Ages. And it was impossible for people to imagine that something that deadly was contagious because up until AIDS, everything contagious could be cured by antibiotics. People were afraid of cancer and things that you knew weren’t contagious. It directly followed a period in New York, Paris, certain cities, of unbelievable male promiscuity. I mean men having sex with thousands of men, not hundreds. And I used to say to my friends who are men, “If straight people knew what was going on, they’d be here with guns to kill you.” But they didn’t need guns because AIDS came. It wasn’t something that caused AIDS but something that spread it. If you have sex with a hundred people a week and something is contagious like that, it’s obviously going to spread like fire. Most straight people don’t have sex with a hundred people a week. So I think gay marriage was a deal in their minds. In other words, they kept saying to people, “We’re just like you straight people; we want to have a family but we’re prevented from having one.” Then it became true; the younger people think of themselves differently than homosexuals my age. They grew up being acceptable, much more acceptable—not wholly. This wasn’t the case for people my age. I lived in a little town, and it didn’t even exist; you didn’t see it, it wasn’t mentioned. And female homosexuality—you never heard of it at all. I only knew it existed because I read books. I knew other girls my age living in even more culturally deprived places than I did who thought they were the only person in the world like that. This is what isolates. The way you think of yourself when you’re young affects your whole life. So this thing with marriage and children is something that never occurred to me.

You said that gay men of that time were very promiscuous.

Beyond belief.

What about women?

Not like men—because no woman, straight or gay, is as naturally promiscuous as any man, straight or gay. The way gay men acted, and still act, is the way all men would act if women agreed to it. A woman would not walk down the street and look at a guy, go into an alley and have sex with him, go away and be happy. Not most women. For women, it’s not natural. But it’s natural for men. Men would like to have a candy store like that. And it’s like a candy store for them. Because the other people they want to do it with agree, “Yes, this is perfect! Let’s not tell each other our names. Let’s never see each other again. Let’s do it this second, and that’s it.” Gay women would never like that. I personally was much more promiscuous than most gay women of the era. I see a lot of these women getting married to women—I see the wedding announcements in The New York Times—and some of them are my age or older; they’ve been together for 40 years. Now they’re finally getting married because they always wanted to. That was never me. I’ve learned not to predict the future, but I promise you you’ll never see me in the wedding announcements.

(Laughing.) You said the main division is between men and women, and you also mentioned biological differences between men and women. Don’t you think biology somehow determines or influences people’s way of thinking—that there can be a division in ways of thinking?

There can be. But I truly believe this is cultural. In other words, from the second a baby is born, it’s treated differently because of its gender. The way people talk to a baby boy is different from the way they talk to a baby girl. The tone of voice is different. It’s very common here for people to talk to little boys and call them ‘little men’. No one calls a little girl ‘little woman’. That affects you. It affects boys and it affects girls. The way parents treat their children affects them for the rest of their life. When I was a child, if I asked to do something, and they wouldn’t let me do it, they would say, “Because you’re a girl. That’s why.” After a big family dinner all the girls and women would be doing the dishes, and all the men would be sitting in the living room, smoking and talking. I would say to my father, “How come I’ve never seen you doing dishes, Daddy?” And he’d say, “If I wanted to do dishes, I wouldn’t have had two daughters.” It’s not acceptable for people to say that anymore, and I think that’s the biggest progress made in my lifetime. From the human point of view the progress women have made since I was a girl is tremendous. But it’s not perfect. I think other inequities will disappear if that one does.

This improvement for women coincided with a cultural decline, if I understand you correctly. Maybe there’s a causal link between the two?

No, you’re oversimplifying. First of all, I make a distinction between society and culture. Society to me is how human beings interact with each other. There have been many more improvements in society than in culture if you think of culture as cultural production, as the production of art. There have been tremendous advancements in my lifetime for women, for black people and for homosexuals. Homosexuals always say, “It’s just like the civil rights movement.” And I say, “No, it’s not; it never was” because for homosexuals there was no such thing as slavery. You can pretend not to be gay, but you cannot pretend not to be black. There have been tremendous advancements for women but not equality. One thing that has improved is men. Young men, men in their 20s, as far as their attitude towards women, are much better than men of my father’s generation. Much! And it’s because that’s what they were taught. They used to be taught the opposite.

Maybe men have become more feminized.

That’s true.

There’s a cost for this improvement.

It depends on how much you admire masculinity. Some aspects of masculinity are horrible. But there’s an upside to physical strength in certain environments. If I’m in an apartment building that’s on fire, and they send a woman as small as me up the ladder to carry me down, I’m worried: Where is that big guy to carry me down? That’s the upside. Men are also more violent than women. And you don’t want to fight in this culture, not in New York. So yes, aspects of overt masculinity have dissipated, and that’s better for contemporary life.

Maybe the improvement in society is causally linked to the culture’s decline?

It isn’t.

Maybe good cultural production needs a terrible social life, wars and earthquakes, poverty?

No, that’s not true. I don’t know, Renaissance Italy was pretty civilized.

But there were plenty of wars going on constantly.

But there are plenty of wars right now!

But in New York…

The actual fear of violence is greater than it’s ever been. The WTC was the biggest loss of human life on American soil since the Civil War—because we were never attacked by another country. There are only oceans around us.

Oceans and Canada.

And it’s good to live next door to Canada. I always say,“I would like to live next door to me because I’m the best neighbour, I’m quiet. And the next best next-door neighbour to me is Canada.” But now many people are in a constant state of fear. It’s not that terrorism never happened here before. It was simply isolated in the sense that it was one crazy person. No ideology.

Have you thought about terrorism, in a non-trivial way?

I’ve thought of it in every way, but only since September 11th. It didn’t seem such a mystery to me like it did to other people.

What was the mystery?

Everyone kept saying,“Why do they hate us? Why did they do this? Who are they?” I think it’s almost impossible for people who aren’t American to understand the unbelievable level of ignorance in this country. This is how the president of the US managed to convince a country that had been attacked by 19 Saudis to invade Iraq. Iraq! But an average American wouldn’t know the difference. Personally, I didn’t feel afraid.

You didn’t think it was the ultimate work of art.

No. I thought that was a despicable statement. I understand what he meant; that was very original, the conception, but it was a despicable thing to say in the face of the murder of three thousand people. And that’s the reason I find a certain kind of artist endlessly annoying. I find that kind of statement… If you are one month older than 14 years old stating something like that, I’ve lost interest. It’s adolescent. But it depends on what you value, whether it’s your own cockiness, which is a teenage value, or what happened, which is a serious thing. And it’s a very serious thing when people misinform people—when the president of the US says,“Now we have to attack Iraq.” That’s a very serious thing—to deliberately mislead a country. And for the country to be so badly educated that you can do it.

Do you mean that the average American is more stupid than the average French or the average Russian?

I’m not familiar with the public education systems in these countries. But it’s hard for me to imagine they could be worse than here. This country’s public education system is very bad, and it has been very bad for 35 years. That’s a long time; that’s many people who are badly educated—to the point of not knowing the difference between Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

Maybe you have bad geography teachers.

That’s more than bad geography teachers. You know, bad governments, dictators, they don’t want an educated population because people might say, “You are wrong.” And if you distract people with entertainment instead of education, most people choose entertainment. It’s more fun. It’s not that I think people used to be better. People are the same. It’s that in certain environments people aren’t allowed to just consume what they prefer. When I was a child, if you had said to me, “All you can eat is candy,” I would have eaten only candies. No one let me do that. But we let the entire country eat just candy from the point of view of knowledge. It’s a childish taste, a non-educated taste.

You smoke cigarettes.

I’m sorry?

You smoke cigarettes instead of having candies.

I’m not saying that I don’t like candies. I’m saying I wouldn’t prefer to eat only candies in preference to all other food, as I would have as a child. And I didn’t smoke when I was child; I started smoking at 12. I’m simply saying that having an ignorant population is helpful for bad governments. If you’re a dictator, you don’t want people to know things.

Do you see a dictator in the USA?

I see that we’ve managed to do this without having one, which is even worse—without force. They did it by exclusion, little by little. The government of the USA right now—the federal government, Congress—is, in my lifetime, maybe not in the history of the country, pretty much the worst.

By which standard or criteria?

First of all by mine. But second of all I would say there are financial interests in this country more powerful than the government, and that’s dangerous. People in Congress basically vote for private financial interests. Nothing is more profoundly undemocratic than that.

To hell with democracy.

You might feel that way, I don’t. I happen to be a democracy fan. I feel almost quixotic about saving democracy. I feel that people don’t understand it. And what people don’t understand about democracy is how artificial it is. It’s the most artificial form of government. You have to teach it to people. It’s not natural. Natural to people is what happens with boys on a playground. A monarchy is natural to people; that kind of pecking, that’s natural. Democracy is artificial; you have to teach it to people. Democratic institutions are complicated; they require constant vigilance and constant effort on behalf of the citizens.

How is it possible to have these institutions if the majority of the public is ignorant, as you said?

It’s not, that’s what I’m saying.

So nothing like democracy is present here?

There is something like democracy; if you compare it to North Korea, Saudi Arabia or many other countries, it’s still more democratic. But if you compare it to the USA of 30 years ago, it’s less democratic. That is absolutely true.

You said this is the worst Congress in your lifetime, according to your criteria. Could you explicate those criteria?

There’s a huge amount of money in politics now; they need a lot of money to run. People in Congress are either rich people with money to run or they’re people who owe allegiance to those who gave them money to run. So they represent financial interests other than their own.

OK, that I already got.

That is not democratic; that is not serving the public. And the Republicans in my opinion are unpatriotic. The day after the Boston bombing, Senator John McCain stands up and goes, “This boy”, the one they took into custody,“ should be deemed an enemy combatant and tried in the secret military tribunals set up by George Bush.” My response to that is, “You are unpatriotic; you don’t believe in the institutions of democracy.” The institutions of democracy are perfectly capable of trying this guy. And one thing about trials here is they’re public. We don’t have secret trials. We have public trials where anyone can see what’s happening. That’s the most important thing. My feeling was: this boy did something heinous, no question, and I am not defending him. I’m defending the system. And the system is: this boy goes on trial like all other Americans go on trial. Everyone watches the trial, and we make sure the trial is fair. And everyone said to me, “OK, you say that because you care about the boy.” No, I don’t care about him at all. The second you blow up people in the street, you’ve lost your claim on my sympathy; I’m not sympathetic to you. I’m sympathetic to the system. It’s a good system. But it’s very bad to pervert the system. It’s very bad that five minutes later John McCain jumps up and goes, “We should try him in a secret court.” To me that’s despicable.

How would you characterize your sense of humour? You’re sometimes called sardonic.

Yes, I think that’s not inaccurate.

Who do you consider the funniest author?

Oscar Wilde.

Charles Baudelaire once said that to sleep with an intelligent woman is a kind of homosexual act.

I’m not surprised. That’s exactly the sort of thing one hopes will disappear, this notion. Because this notion means that an intelligent woman is a man. Perhaps you believe this, but it isn’t true.

And all you say is true?

Let me put it this way: everything I say I believe to be true. This isn’t natural for everybody. Many people say things they know are not true. I believe them to be true. The things I’m telling you, the actual things, are true. If I tell you I’m from New Jersey, you’re not going to find out I’m from Ohio. If I tell you I’m 62, you’re not going to find out I’m 68. Facts that I tell people are always true—and things I believe to be true. For instance, when the financial crash happened, numerous people called me to say, “You said this two years ago. How did you know this?” And I said, “I just pay attention to things.” That’s all. I pay attention to things. And most people don’t.

Questions by Arnis Rītups