Reģistrējieties, lai lasītu žurnāla digitālo versiju, kā arī redzētu savu abonēšanas periodu un ērti abonētu Rīgas Laiku tiešsaistē.

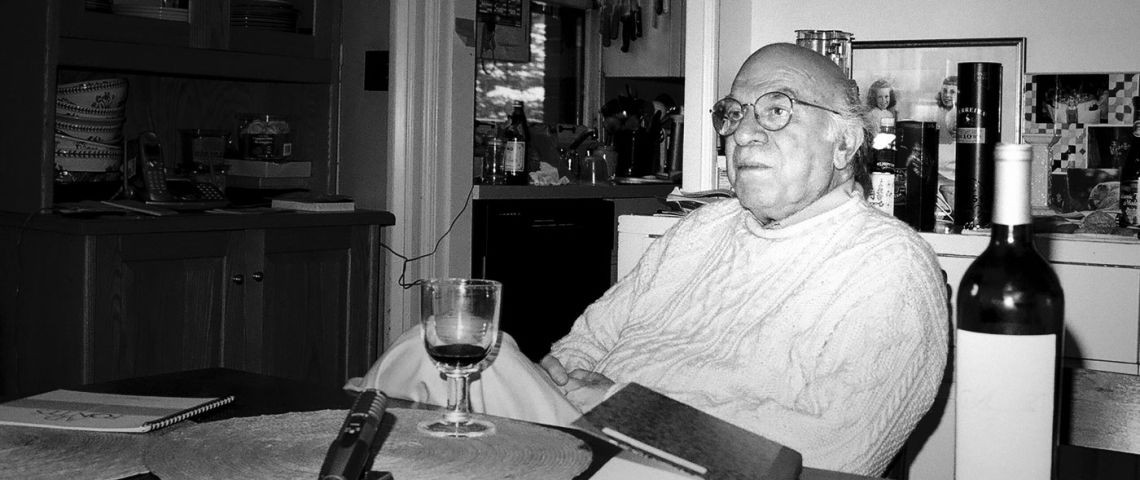

Many consider Stanley Cavell one of the most original thinkers in modern American philosophy. His voluminous writings over the last fifty years include an influential reading of the later Wittgenstein, but also address themes as diverse as cinema, opera, Shakespeare, and Romanticism. He characterizes what is probably his most significant work, The Claim of Reason (1979), as an attempt ‘to bring the human voice back into philosophy’. This is a voice that had all too often become ‘lost in thought’ as philosophers digressed from the ordinary ways we talk about our lives. Seen from a different perspective (explored in his writings on Thoreau and Emerson), the human voice is endangered by the pressures of conformity. Given this preoccupation with voice, the decision to tell his life story in his most recent book, Little Did I Know (2010), demonstrates perfect philosophical consistency—and it is especially fitting that we now hear his voice in dialogue.

Adam Gonya

Are you a philosopher?

It’s a very good and interesting question and maybe we’ll decide that at the end of our conversation.

Well…

I have a PhD in Philosophy…

That does not naturally lead to someone being a philosopher.

Nothing does. Just the way they think does. There is no sure way to know that you are going to end up being able to philosophize.

When you say that the way you think does make one…

is…

…philosophizing, could you characterize that way of thinking?

If I could, it would be just the way I characterize it in this moment, tomorrow I would characterize it in some other way or in 15 minutes I’d no longer like it and that too is philosophy. Of course, I could say that philosophy is the exploration of the fundamental beliefs of human beings, so I’m interested in that. And if being interested in that makes you a philosopher, then I’m a philosopher. But it interests me that you can’t tell from the form something takes any longer whether it’s philosophy. Is philosophy systematic or anti-systematic? The problem with us is that it’s exactly both now. I don’t see how you could be a philosopher without reading the history of philosophy. On the other hand Wittgenstein—who is for me my most influential philosopher of the 20th century—knew very little philosophy in the historical way. He claimed that he knew very little and I believe it. I don’t really know how much philosophy Descartes knew…

He knew fairly much but he was a great liar, Descartes. He said he had not read Augustine, but Wittgenstein picked up Augustine and it could not be done if he hadn’t read a lot.

Almost nobody thinks that Wittgenstein read through the Critique of Pure Reason; however, it’s clear that he did read Schopenhauer. Well, if you are Wittgenstein maybe to read a summary of Kant that is given by Schopenhauer is enough? Who knows what it is to read enough…? By the way, as soon as there is a philosophical system there is also an attack on the philosophical system, so… So I can say there are two kinds of philosophers I know—ones who are interested in what philosophy is and ones who hate this question and never raise the question for themselves. I belong to the first; I would hardly know what it’s like to try to think philosophically without asking myself what I think I’m doing. It’s within philosophy that philosophy becomes characterized. It’s not worth hearing what philosophy is apart from someone who is trying to do it and to answer in the moment.

What you said now already tells something about the nature of philosophy—that it cannot be characterized without philosophizing.

Or put it in another way, I believe that it’s like and unlike everything else, but it is a path, it’s a path of thinking, it’s not science, it’s not quite art, but it partakes of all these things, and it still exists. Why bother whether there are plenty of people who are not interested in trying to characterize whether what they do is philosophy or not, as long as it’s clear in thinking.

Well, many of them try to be scientific…

Indeed, so many that it’s worth Wittgenstein’s time to say—it’s not science.

There has been a perpetual, eternal strife between philosophy and religion and certain dimensions of it. Would you say that it’s necessary for philosophy to be in such a critical stance towards religion?

Well, it’s in a critical stance against everything and religion is one of those things. But I take the spirit of your question to mean—doesn’t religion have some special role in philosophy’s effort to criticize everything human, and I’m also inclined to think so, and what’s special about it, I think, is the question of where authority lies. If I say intellectual authority, that seems to me too little; it’s something about how far I’m able to really take authority over my own mind…

By “take authority” you mean what?

To be able to justify my own beliefs. I can never yield the question of what justifies my opinions about the world, my claims to know, my desire to believe this or that by anything other than myself.

Who is this ‘myself’?

At least it’s not God, and it’s nobody else who claims to know anything. Maybe that’s what in some way Descartes’ cogito partly means to me… that my thinking is mine, I can’t allow however fundamental anything other than myself to be the ground of it, the authority for it, the justifier of it. That’s a philosophical claim.

To claim that my thinking is mine and to claim it not in the banal sense—that I am doing it—but that it is mine in some more substantial sense, it seems that there is some effort necessary. Could you describe what it is?

You asked me a general question and I gave you a general answer. In order for this general answer to have any weight, to be useful at all, it should characterize the things I say, the things I write and it would be a kind of answer to a question—why do you write the way you do? I’m always asked this question, and I’m told that it’s not the way other people write, it’s too personal or too literary. The true answer, the general answer to this is that I’m showing the thoughts are mine, I’m putting them in exactly the way I find they occurred to me, I’m not even asking for your belief in them. I’m trying to find out whether I mean them, whether I take responsibility for them, yeah… the extent to which I live them, as opposed, for example to them being an invitation from somebody else. There are all kinds of voices in one’s head and sometimes when you write you also realize… what makes you correct something you’ve written? It’s not because it’s not pretty but because you don’t mean it, and to be able to mean it is a part of what I mean in saying in a generalized way—they are my thoughts, it’s mine! Different philosophers have different ways of saying this, too. It’s what Socrates is talking about when he hammers away with his argument—to find out whether people mean it or not? Let’s say, Euthyphro tells him he’s going to report his father to the authorities, and it can look as though Socrates is trying to talk him out of this. Of course, he is trying to talk him out of this, but the main thing—he’s trying to find out whether he really means this that it’s a good thing.

One aspect of whatever Socrates did was that he did not write. Why do you think reading and writing is necessary?

First of all about reading. There are two implicit claims that philosophers—if they don’t say it, exhibit by way of preparing themselves to write. In one a philosopher claims to have read everything, and in another a philosopher claims to have read nothing, and probably the two philosophers who have influenced me most enact these two moments. Heidegger claims clearly to have read everything and Wittgenstein, well he does not say that he has read nothing, but there is no indication that he ever read a book all the way through. If he quotes Augustine, it doesn’t necessarily mean he has read him, maybe he is sitting in the dentist’s office and the dentist has St. Augustine on his coffee-table… What’s common to both of these is that philosophy does not speak first.

Somebody has already said something…

It’s not just that somebody else has already said something, though that’s a very important part, it’s as important as the fact that the language is already there. But I mean something a little more specific: a philosopher has to be stopped, somebody has to say it to you, somebody has a question, somebody has an assertion. One of my recurrent images of this is the opening of the Republic when the slave runs up and grabs Socrates by the cloak and stops him from leaving and says—my master wants to talk to you. Otherwise, of course the voice can be in your own head. And it can stop you. I don’t know whether Socrates is in trance when he stands outside of the building before the symposium for hours, and he just stands? Is it because a voice in his head stopped him or he is in some other sort of trance? But I don’t need to know, so far he has not said anything. Do I want to say that you can philosophize without saying something? In philosophy you can’t say anything unless somebody has already said something, demanded a response. Sometimes I find myself saying that the first virtue of philosophy is to be responsive, and that I also get from the figure of Socrates. At the end of Symposium he is still talking, responding to things, everybody else is asleep…

drunk…

…but he is still responding to something, we have not got to the end. Here I’m talking about philosophy that begins when somebody stops you in the street… Philosophy should not claim to know something that everybody doesn’t already know; they just don’t know they know it or they are repressing it, or they want to forget it, or they are confused about it. This is a reason why writing is or should be suspicious—that it claims to be telling you something that you don’t know, it comes from afar. And that’s a danger, philosophically a danger; it’s very important to know things but it’s not important for philosophy, on the contrary.

When you say that philosophy begins by somebody asking, or grabbing you by the hand, it sort of implies that philosophy is a discreet, discontinuous activity—it starts and when you have answered the question it’s over?

I answered your question what starts philosophy and said that philosophy does not start itself. Now your question is what stops it once it gets started. One of my favourite texts is Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, for me it is still alive. It does not mean that it’s alive for me all the time; if I don’t have a question for it, it’s not alive for me. But it has probably inspired me more than any other single text of the 20th Century. Part I, the major part of it, has 693 sections, so I say that philosophy in this book starts 693 times and it stops 693 times, each time it comes to an end. It does not mean a metaphysical end, it does not mean an absolute end, but it ends that question, and as far as we know every question produces another question or ten more questions in which case it starts again, but you have to start it again. At that stage once it’s started you can yourself become your own interlocutor, you can become dissatisfied with yourself, with what you’ve said. That’s dangerous, you’ve put yourself in the world now, you can pause but you can’t get out. So you may yourself keep asking these questions. This doesn’t answer why I write about the things I write…

Do I understand you correctly that thinking also is not continuous, it comes and it goes?

Yes, I do think that.

So when a question appears it can come, and when the question is exhausted it disappears. What happens in those breaks when no questions appear?

Yeah… (Long silence.) That’s a nice question. What Emerson would say happens between those moments of thinking is life. Literally he says this… In this essay every American kid reads, he says we don’t know how to think, we just have this idea and that idea, thinking is, with us anyway, always only partial, it comes only in fragments. The only whole thing, the only complete thing is life. He says this about life because he really wants to say something about thinking. Because he wants to have something that’s whole. Well, life is whole, I’m whole, but my thinking is only partial. ‘Partial’ in English means two things: things in parts, and also ‘I like it, I pick it out as something that I have a special relation to’. Heidegger says this thing too, about thinking, that it’s motivated by desire. I have the feeling I’m making myself obscure. I’m trying to answer honestly but I trust you to know that for anybody to answer that question—what is philosophy—is going to be difficult, unless they are willing to say that it’s an attempt to understand the progress of science and logic, and the foundations of these matters; these are the highest intellectual enterprises that exist and to understand philosophy, the ground on which they stand, is a work of a lifetime. It’s easy to say and I can repeat it.

How can this quote from Emerson be your answer to that question what is between those thinkings? Is it your answer?

It’s a little abstract to be my answer. I liked your question and I did not want to answer much what happens between those times when you are thinking.

Well, for me life in the sense that Emerson uses the word is sheer abstraction.

Yes, of course. Well, I’m really telling you I don’t have an answer to what goes on between those moments of thinking. But philosophers have answered this question. Hume says—how can I stop thinking? I have discovered this horrible thing, namely that we know nothing, how can I stop thinking? If I don’t think about it then I won’t know it because in order to grasp this fact that we do not know that there is a world of objects, that there are other people, that there is a God that we don’t know, I have to think about it, I can prove it to myself. Because if I don’t think about it I’m not tortured, so all I have to know is how to stop thinking about it. And this happens, he says, when he goes and speaks to his friends, he leaves his study, goes out and has a glass of wine with his friends and plays backgammon, and then these terrible thoughts go away and the knowledge that he just got in his study fades and he is able to live. It’s the sort of scene that I make a lot out of. It says that thinking is dangerous, it isolates you; and that’s why it’s nice to go out and have wine, and it’s nice to see that others exist and I exist for them—even if when they leave and I go back to my study and loneliness, I will find out it was all an illusion… Another instance is Pascal, he’s discovered in religion very difficult things abut human wickedness and human weakness. He says that he feels he knows it’s the truth, and the only escape from this knowledge is distraction, amusement, backgammon… But for Pascal other people would be a distraction, too. So it’s not as though philosophy does not have to deal with this question about what’s happening to you if you don’t philosophize, how can you escape from philosophy? That interests me as much as how can you do philosophy. Of course, since we are university teachers we have to think about how to motivate students, how to make it interesting. I think it’s a weak position or anyway it’s a defensive position, you have to show your students that it’s so interesting! And moreover you do it all the time… the question is how to stop.

How do you stop?

The way everybody else does—sex, art, life… and then all of these things cause philosophy, too. Because they don’t last forever.

Is there anything that doesn’t throw you back into philosophizing?

No. As long as there is any freedom left in the soul then probably nothing… I’ve never had really terrible things happen to me but as long as there is any freedom you’ll find that the impulse to philosophy won’t vanish.

Is there anything that could take away your freedom in this sense?

Can a hero outlast anything that a villain can do to them? I hope I never have to find out.

I can easily imagine philosophizing as speaking, as a conversation, thinking on one’s own and being tortured in his loneliness of thought, but why write? How is the impulse of writing related to philosophizing?

(Very long silence.) You can understand it if it’s conversation…

The example of Socrates allows me to understand—you read, you speak, you are in a conversation, you don’t necessarily write.

You might expect the answer to be that it’s a way to continue the conversation with yourself which in some way it always was anyway. You might get such an answer from Descartes at the opening of the Meditations, you remember he says it’s been a long time, I’m finally alone and now it’s my chance to take apart my whole mind… But suppose you turn it around, and you think that someone might also write philosophy out of either an inability to be alone, or a terror of being alone, or just put it neutrally—just continue the conversation when you find that you are alone. But what would it be like if you tried… (Long silence.) Yes, I would like to follow that out… a fear of being alone… What would it be like to try to only think alone and not write? One thing you could say about Socrates who didn’t write, is that he needed the other; you don’t think to say this about Socrates, because he seems so completely independent, he seems the independent man capable of doing anything by himself, but maybe this business of not writing is that he needed people, more than any other philosopher.

Sure he needed other people; he was in love most of the time.

He was rather withholding, he would only go so far. But yes, this closeness with others… It’s a question not to take for granted why philosophers write, but you can also ask to whom the philosophers write. It’s to somebody. I’m not talking about writing dialogues which are on the whole not very interesting, except for the great ones…

Plato’s dialogues are excellent.

Well, I said except for that. He doesn’t need us to praise him, it’s like saying that the Sun is very interesting, it does its work awfully well. (Laughing.) Another question is how can conversation satisfy a life? But it’s still alive, this depth, this craving, this glamour of conversation, it’s still alive in philosophy, it’s like a mystery, because it’s still a mystery how philosophy can exist in the university. I know most philosophers of my generation, it’s a small subject… I mean in the States… I know therefore that there have been four philosophers in my generation who had a real influence on philosophy, made a mark on a large number of people and never wrote or wrote so little that it bears no comparison to how much influence, how fertile their minds were… One of them was Burton Dreben, a student of Willard Quine. Quine thanks him in two dozen books of his for all the conversations. Another one was Rogers Albritton, he was at Harvard when I came; he was an important reason why I came. They published in their lifetime maybe two, three papers and for the last thirty years they didn’t publish anything, I mean not a syllable. Another is Sidney Morgenbesser at Columbia, he published a number of little things, but he talked to people about everything, he was very witty and he needed to talk. They all needed to talk. And the fourth is a recluse, Thompson Clarke who didn’t need to talk. My book The Claim of Reason is dedicated to him. My closest philosophical friend happens to be married, but he is a recluse with his wife… He withdrew from the world more and more. He published two essays, actually three, one of them was only about two pages long. I know he writes on little pieces of yellow notes and he has thousands of those in his study. Philosophy attracts strange people. Philosophy is a subject in which without writing you can be an influence on the field as such. It separates us from any other field.

You have said that to philosophize not out of love is questionable. If philosophy is so close to passion could we even conceive any institutionalized form of doing philosophy—like teaching, reading, studying—which would not suppress this passion itself, the love?

No. Probably not. Philosophy is a very unsociable occupation, it upsets civilized discourse. One image of philosophy is symposium, this is very civilized, thinking together and speaking, but also joyfully, with wine, drinking together. But it’s perfectly natural for a philosopher to say ‘you are crazy’ to another philosopher if his argument is no good. But argument is only a stage in thinking, although it’s taught often in the university as a kind of polemic when you are taught to argue in order to defeat views. It’s certainly part of thinking, but for me philosophy does not end with anybody victorious. Nobody should be defeated in a philosophical argument exactly because nobody knows anything that the other people do not know. So until you get to the point where there are no longer… You know, it’s a polemic, there are two sides, it’s a war until you get to the place where that’s finished and everybody wins, or everybody is equally defeated. Then you haven’t come to the end of a philosophical argument.

You are not very impressed by the way philosophy is taught at the university.

Many people approve of what I do, but it’s often a puzzle, why this way? Why so much literature, why Emerson, why film, why Shakespeare, you don’t need these things in philosophy. It’s true you don’t need them but…Wittgenstein comes closest to this ideal of mine that philosophy is not polemic. There are plenty of mistakes you can make, it does not at all mean that you cannot be inconsistent, but it means that it ends in a kind of perception, each time; you have to test whether it is really a perception or whether you are just beaten into silence; silence in itself is nothing, it depends how you got there. Well, university. Yes, I think that philosophy is not at home in the modern university the way science is at home there. The whole institution is for the kind of learning that is done in a systematic way, and everything that cannot be done in a systematic way is slightly awkward in it… In literature, what’s taught is criticism and history, and these things can be done with some quasi-scientific point to them. But philosophy is nowhere at home, so it almost does not notice the fact that it’s not at home in the university, or it makes itself into science. It can mean logic, history of analytical philosophy, the application of logic to philosophical problems. If it’s not that then you are philosophizing with your students, you are not quite teaching the way people teach in the university. You are not giving up your authority, we come back to this,it’s not that I am the authority but no one has more authority than I have, and vice versa.

Most philosophers I can recall would say that philosophy is some sort of passion, one way or another. I can only recall Wittgenstein who said that philosophy is illness…

Well, he says that philosophy is a kind of therapy, we treat a philosophical problem as if it’s some sort of disease. Hume says it’s a malady from which we can never recover. He says this about scepticism… But go ahead, please.

You said that philosophy is about asking torturing questions. How should the world be in order for philosophy to be a torturing exercise rather than a pleasurable or whatever?

I don’t know that there is any world, we could go two ways about this. I might answer it by saying that in a world of perfect justice there would be no need for philosophy. We are talking about the end of Republic when Glaucon says, “No I don’t think that this city that we built exists anywhere”, and Socrates says, “Never mind, it does not matter, that’s the city in which you could philosophize.” And if it’s a city of perfect justice, there’s a paradox about this, what would you philosophize about? What need would there be for philosophy? Even if you could imagine a city of perfect justice, the problem is—there are always people in it. They are going to be dissatisfied even with the perfect justice, human beings are such that they know how to make themselves unhappy. Wittgenstein’s implied word for this is restlessness, what he speaks about is that philosophy brings peace. The problem with this is that this peace lasts for a moment, it is lost the moment somebody has another question, and there is always another question, the human being knows how to make itself restless. Restlessness appears in the first paragraph of St. Augustine’s Confessions… I’m restless as long as I’m not with God. And if in philosophy there is no God… This is a syllogism: man is restless without God, minor premise—there is no God, conclusion—man is always restless.

Well, the second premise can always be doubted…

Of course, and it must be! As far as philosophy is concerned it’s bound to be…

But most of the academic philosophers take it for granted—it’s a childish game, there is no God.

Yes, I know…

You know… I’m well aware of this, Socrates. You are right, Socrates. (Both laughing.) I’m not giving you what you want… I know it.

No, you do! This will be a jump to another subject. Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz writes that this is the worst of all possible worlds, and well, we know Leibnitz’s attempt to show that this is the best… If I ask you as a philosopher—between these two answers, where would your worldview be, or would you just dismiss it as sheer rhetoric?

No, I would not dismiss either of them. I might want to ask myself what’s in it for anyone to insist on either of these. What is the food, where is the nourishment? I can see no nourishment in the idea that this is the best of all possible worlds unless this idea is a part of a theodicy! If God is not at stake then you are a fool if you think that this is the best of all possible worlds. We could think of thousand and thousands of ways in which it should be better. But if God is at stake then you may have some question about it, why it can’t be better? Why, given that He could have made it better, he did not. That it’s the worst of all… you should bite your tongue. I still take Shakespeare almost as close to divinity as you can come, and when he says there is no worst, as long as you can say ‘this is the worst’ there is no worst. And he has just finished this soliloquy about how this is the worst of all possible worlds… and in comes his father who has just had his eyes gouged out, walks on the stage, and almost superstitiously, as though he has produced this demonstration that something is worse. If you say, this is the worst of all possible worlds I have a feeling that you are not talking about the world but about something that’s happened to you, an extremely personal thing. If somebody else’s father came in with his eyes gouged out it’s doubtful that the first thing that would be on your mind would be that this is the worst of all worlds.

In your autobiographical book A Pitch of Philosophy you say that your father who had lost his faith in God told you that you should find it out (about the existence of God). I did not see in the book any trace of the development of this question… Has there been any in your mind?

It’s an excellent question. You are on to me. I wanted that story to be there even if the only thing I can say about it in the end is to give some excuses about what my stance is about these questions. Often I use the excuse that philosophy has nothing to say about this question, it’s the limit from which you can never return, like death. Philosophy can talk about death, it has to bring death into the room, it must recognize human finitude, we are all going to come to an end, and philosophy has to keep this in mind. Almost everything I do in philosophy is derived or I would like it to be derived from this remark: speech comes to an end, the body comes to an end…

Thought comes to an end?

Yes, but specifically in each thing. Explanations come to an end somewhere, says Wittgenstein. It’s a casual remark like most of what he says and suddenly it strikes you what the implications of these things are. But philosophy cannot bring God into the room. I think it cannot keep God out of the room either. If I say that this question is open from my point of view, I don’t want it to suggest that I am open-minded about this question, it’s like agnostic, you don’t want to say you are an atheist, so you say you are agnostic, that’s not how I feel about this. Heidegger comes close to an idea about it. Anything I could say about God probably has to include Nietzsche’s immortal remark about the death of God and that we live our lives in an aftermath, in a sort of beyond of a certain believing, but well, to draw out the implications of that… I am somebody that does not prevent myself, when I want to, from evoking the name God—when it wants to come up, I let it come up as if I’m waiting to see what I think about this; the death of God means we no longer have a relation of a kind to God that presumably human beings, at least in the Western culture, had for a fairly long period of time. I am also caught by Heidegger saying—anything I say about this can be overthrown at any moment; I use these words, I use the word soul, so does Wittgenstein, I’m grateful to him for these encouragements. The human body is the best picture of the human soul, he says; okay, Wittgenstein, what do you really mean by soul? Why don’t you just say it’s the best picture of the human mind? I don’t feel I even have to answer this. That’s what he wants to say. It’s self-evident that it’s not something he’s asking you to believe. If he is not asking you to believe it he does not have to justify it. I say it because I want to say it. If you don’t want to hear it, don’t hear it. I put these various remarks about God to see what I think about this and I am prepared to say it may be all over with me, depending what God wants to do with me. If he reaches down and grabs me wherever God grabs you and does something with you, then that will be that. But that’s not an open question for me, we’ll see what happens, that’s not the mood in which I say that. If I could tell you the mood in which I say that I use the word, it’s almost a temptation. Samuel Beckett in Endgame, speaks of the uses of the word God as though they were some sort of curses… The main conclusion I draw is he speaks of a world in which we can only use God’s name in order to curse—goddamn you, is the most famous of these. And that that is in itself a curse that we live under this curse, that we can’t stop from using the name of God and we always use it—as the translation goes—in vain. It’s a commandment… you shall not take the name of the Lord, thy God in vain, that’s the first commandment; what that means—don’t curse. Beckett is saying in effect that this commandment is impossible, every time you say the name of the God, it’s in vain. When I say the question is open for me I mean what would it be like if I suddenly discovered it’s not in vain, what would happen to me? I sometimes go to a synagogue… Yeah, I was born in a large Jewish family, my father lost his faith and I knew it, it’s one of the first things I knew about him. I talk about this, the kind of questions that can only be answered in an autobiography… A very important moment in my life is on a high holiday, Yom Kippur, atonement when you ask to be relieved of all the sins of the year, of all the terrible things you’ve done so that you can be written in the book of life and live for another year, not be punished, I saw this as a kid in an orthodox synagogue in which largely all immigrants, my parents came from a small Jewish village in Poland, they came for all the obvious reasons, you could say they came to get work, they also came because the Cossacks were going to kill them. And I said—this man standing in the corner, I understand why he is here, it’s very hot, and this man has a coat and a big shawl over him, and he is all shaking because he is obeying a commandment—you have to pray with every bone of your body—so he is moving every bone, he is praying… I say you don’t believe what that man believes…

You said to your father?

I said to my father, yes, so why do you come here? I understand why he comes, but I don’t understand why you come. And he said, to his credit, I don’t believe what that man believes, but I come here for my father. And I said—but your father does believe? I did not point to his father, but I was willing to say for the sake of argument I mean his father came to the synagogue three or four times a day to pray, and he had a beard and he had a hat, and he did all those things which you are supposed to do—and you do none of them! So I ask myself and I repeat this question to you—my father does not believe, but he comes because his father does believe so the implication is—why do I come? I hope I didn’t say, my memory is that I left the question there; my father was quite intelligent and he realized that the next question had to be—it can only be one of two things—I didn’t say I come for my father because my father believes; I come for my father. And my question is—is this a good enough answer? I know that this is not a good enough answer for my children, they’ve all been taken to synagogue by me and my wife and for them… at both of their bar mitzvahs I said—I do this because I regard it as my responsibility… The way I have lived they should so far do what I have done in my life, but now it’s up to them, they have a choice whether they will continue to say they are Jews or not. I don’t have a choice because… one way of expressing is—I was alive when Hitler was alive, and therefore I could never say I am not a Jew, but they can say—I’m not a Jew, I am an American. I wonder if that’s true, but they have my permission, I am able to say, “Don’t go to the synagogue for me, you have to mean it.”

Questions by Arnis Rītups