Reģistrējieties, lai lasītu žurnāla digitālo versiju, kā arī redzētu savu abonēšanas periodu un ērti abonētu Rīgas Laiku tiešsaistē.

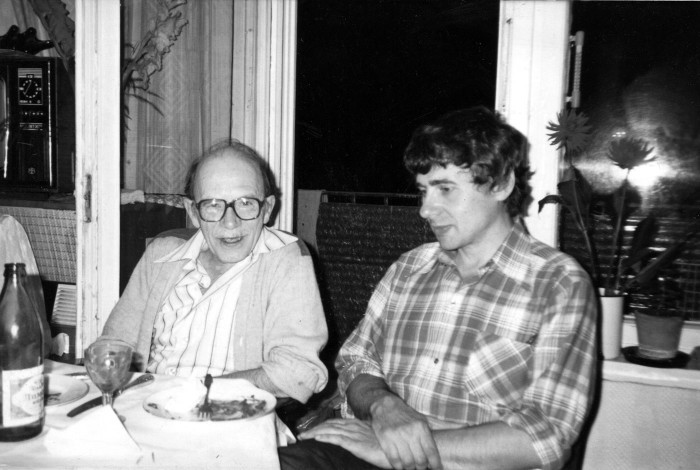

I came out of Gefter’s funeral in 1995 to become a political technologist but he came back to me after I left the Kremlin. It was not the first time that we met again at a pivotal moment of my biography. Every encounter with Gefter changed the way I looked at the world and myself.

Our conversations started towards the end of the Novy Mir era when pro-Soviet and counter-Soviet intelligentsia came to a consensus. At the time, Gefter was a famous and respected Moscow grandee.

I met him in 1970. He was being expelled from the Academy of Sciences. My commune fellows and I tried to explain to him who we were and what we wanted, but I am not sure we were clear enough. Before leaving, I left him my essay on the mystery of the end of history, and received an unexpected response upon returning home to Odessa. In his letter to me, Gefter courteously rejected my nonsensical phantasies about Marx the Humanitarian. Mikhail Yakovlevich unfolded before my eyes a more dramatic vision of the history of European Communism. We started exchanging letters on history.

Gefter emphasized the explosive ambivalence of the Russian Empire as it was constructed by Peter the Great. The tsar not only reformed and modernized, he re-established the Moscow Tsardom as a new Russia. The central mode of the new state was the claim it laid to any person as its subject to an unlimited degree. A man was turned into a mobile and commanded asset of government—its feeble, even if noble, servant. Gefter would be more straightforward: its slave.

To westernize the Russian feudalism in the way he wanted, Peter the Great invented a new model of vertical and horizontal slavery. The agent of modernization was to become the slave of the Empire. Which did not prevent him from perceiving himself a free person within those limitations. What sense does Gefter make of this? If you apply the popular internal colonialism model to Russia, its citizen turns out to be a colonizer and colonized at the same time. Even more so: the wave of the most freedom-loving citizens, trying to flee from serfdom and imperial control (Cossacks), migrated eastward and southward, thus becoming the vanguard of the internal colonization. The empire reached every little settlement in Taiga, every fishing village on the coast of the Pacific, and crossed the Dnepr floodlands of Ukraine on the shoulders of those trying to escape it. (The corporate colonization of Poland and Finland was meant to be a privilege in that system.)

In that situation, one could either join a secret Decembrist revolt or pursue solitary, sombre, and uncompromising thought, like Petr Chaadayev. However, this thought would still become a claim on intellectual power over Russia. Gefter was right to notice that there is a close link between the powerless Chaadayev, who was declared insane and humiliated by the police, and the political claims made by Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin).

Gefter was among the few Sixtiers[1. ‘Sixtiers’ refers to a generation of artists and thinkers whose work blossomed during the “warming” of the 1960s in the USSR initiated by Nikita Khrushchev, and later suppressed under the Brezhnev regime.] who burnt the bridges to become irrevocable dissidents. This drove him away from the semi-liberal circles that stuck with the Soviet regime and sheepishly waited twenty years for Gorbachev to come. Gefter thought Russians had already made their awful sacrifices in the 20th Century, and now the goal was to establish a new inner ‘world of the diverse.’ I agreed with Gefter’s criticism of Perestroika for its superficial and feeble anti-Stalinism.

The talks with Gefter usually started with finding a truth. Even with a chance guest, he would demand to explore the foundation of his judgement and belief. The conversation could set off from a point you made or from some recent news, but it would soon outgrow and overthrow it. A discussion of the intellectual contradictions of the 19th century in Lenin and Chernyshevsky, or of the character of Pilatus in Bulgakov, would soon move on to contemporary actions: tomorrow, now, immediately. The experience of talking to Gefter is akin to listening to a good musical improvisation. Only Gefter was not playing. For him, study of the truth of the past was his way of being loyal to the Russian thinking in movement tradition. (‘Russian’ here stands for global, not ethnic or separate.) The atmosphere of such talks encouraged parrhesia, a Greek word for telling the truth. Conversations with Gefter were a practice of historical parrhesia, and not just some talks about the past. In was a real, not imaginary, conjunction of the main elements that defined my life: history, politics, Russian speech. I personally experienced the way a speech act changes the structure of the event and the political field.

According to Yavlinsky, it was Gefter (via Burbulis) who unwittingly gave Yeltsin the idea of denouncing the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR. He later regretted doing this because he wanted the new Russia to be a confederacy of independent Russian and non-Russian republics and not a unitary state.

Gleb Pavlovsky

It is hard for the reader to become reconciled with your texts, in which an historian’s judgments are always interlaced with self-judgments and personal recollections.

Sometimes you ought to follow a route that seems to you scientifically illegal, individualistic and subjective. A certain man, ‘I’, undergoing formative development in some particular way, put himself into a certain world—to the point of self-dissolution. Then the World started to collapse easily, insulting for the creature self-dissolved in it—the creature that was accepting everything, even the terrible things of this World concerning his nearest and dearest, as a price for something absolutely necessary for everyone, as a particular feature of historical scale.

In doing so he encouraged himself to take actions that, actually, could have negative consequences for him; but he was protected by self-dissolution. Then, suddenly, a collapse, a disaster—a disaster of light-weight recantations that seem to him pretended. What is happening to yourself is naturally regarded on the same scale as the previous self-inclusion, and the explanations cannot be limited by something banal any more. He has to go farther and farther—until he reaches the ends of the World created by Homo historicus where this Homo is acting. The world is collapsing, which brings my thought back to the World where man first came into being: the World that created him and was created by him.

Is it just a personal hardship? Is it just a private collapse alongside the general collapse of the bankrupt life that had been previously put to shame by the vile practices of the system? Or is it a global upheaval that I see as undoubtedly universal?

It took me a long time to start calling things by their proper names. I was confused, trying to find an answer within the limits of the speech I was uttering—taking no notice of the fact that my language had started to change and I was losing the ability to write in my original way. Then I started to improvise and write in a different way—with growing determination. Together with other circumstances in the 1950-1960s—contributing in “World History”, working for the Methodology sector of the USSR Academy of Sciences and so on and so forth –it led to the transformation of my whole view of history. At first this view didn’t reach as far as the essence of human history, but it started to be dominated by the images of historic deviations—all those Eurasian centaurs, Plato’s and the Decembrists’ Atlantises, Marx and Lenin’s Russia. That is my cogitative situation as I see it now. What was really difficult? After getting the first answers, I initially adhered to them rigidly and began preaching and teaching them and, as a result, started repeating myself.

Actually, I got stuck at the questions without answers. They are a weird thing, you know. Getting stuck doesn’t mean here that it’s high time they were answered. No, it’s time to question the very nature of questions without answers. Did I overcome those difficulties, exciting my curiosity, when I started thinking in questions without answers? Or, having made a step in this direction, did I get stuck once again?

It’s a judgment from medieval Jewish kabbalism, I don’t remember the author—that evil doesn’t exist, evil is unclaimed good. Wrapped in evil, good acts as unclaimed. And my personal feeling of history’s depletion, its finality, came to me in a very personal way and was connected with a very grave illness I suffered in the late 1950s.

Did history end personally for you or did you cognize it as terminating?

I couldn’t escape it any more. It became an obsession, I saw everything in the light of history’s termination.

And where did you get the idea of the end of history? When we met in 1970 it was already there and we easily

agreed on it. Did it come from Hegel—or from Marx’s “communism is the riddle of history solved and it knows itself to be this solution”?[2. Transl. by Martin Milligan.]

No, it came from the recognition of an intellectual disaster. The disaster was: how did I fail to see what was obvious and what I was participating in? How could I devote myself to what a normal man mustn’t devote himself to? And as I did devote myself to it, now I must explain to myself, why? What led me to it—careerism or fear? Or was it a complex mixture of several intellectual passions?

But what was even stronger, it was my feelings of repulsion towards my contemporaries, that I was concealing. Why did I have such a somatic breakdown? Because I didn’t dare to indulge in the repulsion that was trying to burst out of me. The repulsion of the Soviet people’s hasty pursuit of a collective epiphany. I didn’t let this hostility out, I was struggling with it and overexerted myself in this struggle. Everything in me was rising against this act of making everyone happy through liberation! Contrary to my inner state, everything around me seemed so favourable, even personally to me—my dear uncle was rehabilitated... It all felt so comfortable, but there was already a shadow of doom over it. The Stalin system that had started to collapse looked to me so vast, so terrifying and so global that I rejected the pittance of liberation granted by the authorities. Even in the cases where it really was liberation I was apprehensive of some deceit we hadn’t identified yet, of a trap we would eagerly fall into. But I didn’t let those thoughts out and was still combating them inside myself trying to overcome them. And my shell-shocked brain, the wounds I had got in the battle of Rzhev, failed me.

Why did I reject the “collective epiphany”? Now even the author of this term, Yuri Vlasov, has fixated on the idea of rejection. I did it too then, but in a different way. It seemed to me that I must cease to exist as a man if the chain of the world events where people rose and perished, where the horizons of the world were open and continents were transfigured—where my generation perished in an instant!—was passing away as mere nonsense. I didn’t regret all those things—it would be silly. I wasn’t nostalgic. I felt insulted in two ways: by the pettiness of my involvement and, even more—by the cheapness of the liberation from above. It was a mistake to struggle with these feelings, to keep them inside—and they burst out with a deadly disease. Only this disease gave me some new knowledge of us. When three people in Belovezhskaya Pushcha cancel the Soviet Union—I directly associate it with the end of something millennial: the idea of humankind as an extra-specific kinship of people has left the Earth. That’s the way an idea abandons the world: it leaves—but instead of passing away entirely it creates the Belovezha comic strips with puppets of old-world characters as well as other complicated mystifications of the Homo sapiens.

Is history just “everything that changed with time”? Is there such a thing as “history of the Milky Way” or “history of amoeba”? No. Strictly speaking, history only exists in the singular –world history can only happen once. Beginning with the conventional Judeo-Christian milestone, in its complex connection with Asian nidi, history has been building up as a project of humankind. The project has supplied people with many things but it has proved to be unfeasible because there was a utopia in its embryo. The extra-specific kinship of people hasn’t worked out in the form of humankind—though it still might be realized in other forms. That’s what makes the moment we are living in so dramatic.

Man is playing the past as an invisible and dangerous game (people can’t help playing it). The bet in this game is no more than a meeting. Don’t hope to achieve more—this is the maximum, the ideal! All we need is to meet the past—just don’t try to get into it! Don’t try to substitute the life of past people with your philosophizing, judgment and pathetic exhortations: their life is stronger than yours. The past is stronger than all of you who are living now.

The essential moments explaining a historian’s stumbling-blocks are—the unmotivated emergence of the thinking man; the inexplicable emergence of speech; the incomprehensible spreading of people all over the Earth’s face and bosom.

When we correlate these three things we find a connection: having acquired an ability to speak, people also got the strange property of continuous unlimited understanding. Speech removed the limit to understanding. Understanding becomes infinitely variable, getting increasingly more profound, but also infinitely more laboured for itself as it reproduces the threshold difficulties, the milestones before which there was no understanding—nothing like a smooth flow of thought. Take the sudden emergence of Cro-Magnon man who didn’t differ from us at all—and physically was even better. We must have lost, and are still losing, many of his abilities that corresponded with what he was originally meant to be. His emergence can’t be fully deduced from his predecessors—which means, it can’t be deduced at all. I link it to speech, which is definitely known for a certain negative characteristic: it is fundamentally different from any other, however complex, form of communication. By the way, in proof of this assertion, look how the over-intensive, over-saturated global communication dulls people’s understanding nowadays. By undermining speech itself, it starts to interfere with Homo’s survival.

Considered together, all these issues inevitably form the concept of the instantaneous origin of human being. Of course, it had its prologues, its threshold, its own genesis and it was somehow coordinated with time. From this point of view, what makes Jaspers’ idea of Achsenzeit (Axial age) interesting is not his particular applications of it, but this coordination of the proto-human with time.

It brings us to the thought: what, actually, is history with regard to the existence of man –man already! The existence that was still prehistoric, ante-historic and proto-historic—and that can’t be deduced from anything. It goes without saying that it can’t be reduced to something, but neither can it be directly inferred from the previous state. Whatever role the so-called “accidents” played (and they have an important place in history, demanding to be included into the very subject of the historical), history is unimaginable beyond consciousness. It is unimaginable beyond such man-made cogitative constructions as the past and the future, because, from the point of view of their temporal progress, neither the past nor the future can be reduced to the physicalistic time of the macro-world.

In fact, there are three kinds of time: the time of the macro-world with its calendar-measured flow of time; let’s call it “trivial time”. There is the micro-world where everything acquires the speed of light. And there is the world of human thought: I regard it as recollecting—as there is no alternative way to represent the world’s motion, and such words as “revelation”, “insight” or “night dreams” are unsuitable here. Generally speaking, man’s dreaming is one of the basic properties of humanity, comparable to speech. Reminiscences play a role in dreams, and the very terminology of dreams is essential.

What is important to know about history is that it arises by itself. The past and the future have arisen once. Actually, how could history arise if there didn’t arise that unusual state that is regarded as the state of the past, as that special meeting of the reminiscence that leads us into what is gone? And what is the meaning of the future that is presupposed to be more sublime and deserving than man’s life “today”—in one way or another?

The future is not just something that lies ahead. It is something lying ahead that has been chosen from what has in the past been rejected as defective, from what has gone and will never return. This is the mode of the future from which the true recollection of the past is possible.

Excuse me, but a judgment of the future is always anti-entropic. It is overcoming which establishes the very notion of the future. You can cogitate the future any way you like, imagining it in any vivid, specific pictures! This game forms the basis of many things: by the way, ideology is impossible without it.

While cogitating the future, the flow of time really changes. When you start thinking of what lies ahead, time no longer flows the way it used to. On returning to yourself, you suddenly find out that it had really been flowing in a different way. This alternate flow of time is, actually, the past. If history doesn’t exist, where does this fundamental arrhythmia of time, its condensation, come from? Think of these days, hours or years that are equal to centuries—in the scale of events, in the inevitability of what is going on. But what is a historic event from this viewpoint?

History offers a mode of usurping this parallel world. History is an attempt to build up a human life that can’t consist only of consciousness and cogitating. It can’t be reduced to a-evolution and extra-specific acts of existence. History is an attempt at involving all of life in the act of realizing and telling it.

From this standpoint, history comes into being once. It happens once. Proceeding from these assumptions, we can imagine why it is getting depleted nowadays. The reason is, what used to be considered supreme for the man—cogitation of realization, forced into dissolution in daily routine—has inevitably acquired ominous properties.

It’s time to consider, what is a question without an answer and what is the non-ecclesiastical idea of the parallel world that is closely, intimately contiguous with theology. This idea is not a whim of circumstances. When questions without answers became connected with my essence and my name, it awakened the Jewish spirit in me—in some old-Jewish sense. Svetlana Neretina is partially right calling my views “historical eschatology”, there is a grain of truth to it. But at the same time I shouldn’t push away my idea of the depletion—rather than the end—of history, because history itself is a form of usurpation of the parallel world, that involves transfer of the world’s speeds to the external action and attempts at universal externalization. It’s my favourite passage from Hegel’s introduction to his “Philosophy of History”—about the cunning of reason—you remember it, don’t you? If this is absolute spirit that has no beginning, as it has already come into being, and its activity is returning to self-existent Being from the completeness that lacks reflection to become man—what is lacking here? And when the spirit externalises, it gets stuck in human history and can not set free without people’s support, that due to human nature, called passion, can not be redundant—and the redundant can’t but become a fall, a self-punishment for redundancy! And how do the final lines of The Phenomenology of Spirit sound then? When the Absolute Spirit is returning to itself after its odyssey, after its difficult journey, it returns to its self, that has been equi-acknowledged, equi-revealed by reflection and identified in a relevant form of human mode of life. The Spirit can’t help looking back—and this recollection is also its Golgotha without which it would have been incomplete.

It is a famous quote, commonly known; it is no achievement that it immediately became fixed in my mind, but it has become very personal. I have always been inspired by the mysticism of these words. In 1950s, during the de-Stalinisation years, the concepts of externalization, getting stuck, this passion of chastising became very personal to me. That’s what historical theology is. If man usurps and externalizes the parallel world, it gives us an opportunity to find a clue to the hieroglyph “the future of the past”.

This hieroglyph of yours has always been especially difficult for me.

There is a fundamental disagreement between the future of the past and the two banal concepts: “everything that has happened” and “everything that lies ahead”. It is not that these banalities just fail to define the past and the future: they are perpendicular to them and simply false. There are different speeds here, not calendar ones. The nature of time itself is different here—as well as man’s time. And here is located what resists history—people’s daily routine. It resists by its regularity. And here also lives culture in its eternal argument with history—the argument that is trying to transfer the daily routine to the stage of the performed tragedies, and to move tragedy to coping with grief without blood and victims.

A huge price was paid for ending the Cold War. Let others say that Gorbachev only had to make some concessions to end it. I am saying, if not for Chernobyl, a global disaster,—there wouldn’t have been either Reykjavík, or Malta. And the recent Yeltsin–Bush agreement in Washington wouldn’t have been reached without the events in August 1991. Are we supposed to quit every cold war through a local or world disaster?

The Cold War is two generations of people who grew up within its framework, breathed in its air. It is not just an error that may be peeled off from the rest of life—it is a projection of man as he is. It is human life that breathes blood.

Sumgayit, Baku, Vilnius, Bender—our system has mastered breathing blood. Will it stop at some point, do you think? Or not?

I will say one thing, it will seem weird. I will be glad if I prove to be wrong. Frankly speaking, this contemporary trouble—“the hot spots”, places where man kills man freely,—is a new institution of our authoritative society. They tone up our supreme authorities, giving them a certain role. Let’s suppose that, much to everybody’s joy, all of them will be eliminated, and the Kremlin will only have economic difficulties with a grave social trail to deal with. It is hard to say, what might happen then—while now Moscow is busy: it is “resolving the crisis”.

Many human instincts become obvious within hot spot collisions, from the noble ones to the base ones. One says: I am all for the Russians in Moldova! The other sings “The glory and the freedom of Ukraine has not yet died!”—and so on. It involuntarily forms a mighty political resource for the man in the Kremlin. And there is a great risk that the man going this way might lose self-control.

Take, for instance, what we have discussed—the bloodshed and butchery in Bender. Look how quickly the leaders made up and came to an agreement! One may consider it as a plus while we ought to be horrified. Just to think that in order to come to an agreement, exchanging handshakes and kisses, everybody needs a preliminary bloodshed, a theatre of emergency!

It is dangerous to get used to emergencies. Such a regime easily gets out of control—and it has almost happened.

Russia looks like a picture of calamity. And it is not that Yeltsin has bad traits of character or that Gaidar tends to Pinochet. Can a global levelling disaster start from Russia spontaneously?

This question requires one of the two answers: “yes, it can” or “no, it can’t”.

In the CIS, and now within Russia too, there is a growing tendency towards anti-alternative wars. Having failed to achieve an alternative in development, they try to solve the problem with force. Russia either plays the role of the UN on the CIS territory—or acts like Moscow, intruding in the internal affairs of the countries that have been proclaimed independent. What’s next? Russia thriving at the expense of Moldova and Ukraine, or Asia expanding back to the North at Russia’s expense? Here are the acute questions touching upon today’s reality. Will Russia’s population agree to it, taking in consideration human losses, will others agree? And when this new angel of good, Shevardnadze, arranges a “peace march” to Abkhazia—what shall the Abkhaz do? Give its participants welcome gifts, treats? They are inviting Russian generals—I don’t blame them. What is unclear is the cardinal question: to where are we returning—to the 10th century? To the 18th? Christian countries want to be with Russia, while mountain peoples, that set an example of anti-expansion resistance in the past, can still thrust us back to the time of Imam Shamil and Hadji Murad. Is that impossible?

Russia as the threatened niche of the World is the most dangerous country for the World now. Following this thread I come to the conclusion: only on becoming a World in itself can the Russian space of Eurasia pass over from the imminent prospect not to be to the realistic prospect “to be”. In so doing it will also make a decisive impact on the turn of the World to the global prospect “to be”.

There are problems that can’t be solved by our means. Their unsolvability hasn’t been confronted by those who could responsibly deal with them. That’s why these problems are being announced by such characters who promise one person an opportunity of self-fulfilment at another’s expense. You may keep saying that it is fascism—yes, it’s fascism. But why should the world fear Zhirinovsky if the Kremlin doesn’t fear him?

The world must understand that it won’t help itself by investing in people like Gaidar. It should invest in Russia’s dissimilarity from the West. But first this dissimilarity should make itself manifest through an alternative programme, speaking the language of the majority of people.

You are right, the World can’t possibly put up with the disappearance of a state that is a member of the UN. But under what sign does it interfere? It’s grotesque: they intrude in Somalia under the banner of humanitarian aid. Under what sign do they interfere and kill people?

There are a variety of grounds, not exactly formal. Protection of the population, for instance.

Which brings us back to what we started our talk with. The problem is, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an optional and deliberative document, it only puts forward a suggestion. It must be followed, at least as an imperative—but as a declarative imperative. It declares the primacy of international law over domestic law, and the primacy of the human rights principle over sovereignty. Then the parties must be forced into an agreement. But—who cares?

It is possible to establish a blockade of Serbia, but the blockade of Iraq had no effect. And who will establish a blockade of Russia? If the Kremlin follows the path of large-scale blackmail—how are you going to blockade Russia?

This mechanism doesn’t exist. In the case of Yugoslavia and Somalia it is essential that they are small and have no nuclear weapons.

Exactly, and even they are too hard to control.

The hour of America is coming inevitably. But what are the Americans like? What can they do? They can gather a coalition of fifty countries and, holding the victims’ hands, destroy one country. And even that is not quite possible—have they achieved anything in Somalia? At some point the American hypnosis will stop working. Now the reaction may be deviant. It is supporting the idea of the new isolationism.

By the way, Zhirinovsky, putting his demagogy aside, is actually an aggressive isolationist. There has been an opinion poll, recently conducted among Russia’s city population, which was quite representative. The majority of people chose “the strong Russia” as their first priority. Not “well-being”, mind you! Another 41 percent prioritized independence from the West, and some 12 percent—even rejecting help. Russia within its contemporary boundaries is a huge space unprecedented in history. It is also a superpower having sufficient weapons of mass destruction. The Cold War has been stopped but it doesn’t end. The world snaps shut. It becomes a monoworld, with one predominant system of government: it turns from two-polar into single-polar. It will do no good and provoke one crisis after another in international relations. Hence the problem of finding a place for new Russia in the changing World. Russia must find its identity, beginning with the elementary: feed itself and find its place in the World, ending with the most complicated and important: to save the World from the total disaster. The problem of changing the World, with changing Russia participating in this process, should be tackled separately. It takes time, knowledge, specific contacts, maintaining personal connections with heads of states and governments. It is the vocation of a head of state: to be a guardian; to establish the new status of the World and the status of Russia in this World that is changing dramatically to something as yet unclear.

But look at the other side: the shut, single-polar World of “the West’s victory”—what does it mean for us?

Russia is a prototype of the World that might never come into existence. Why can the World still fail to be fulfilled? Because the gigantic levelling trend of the West does not only prevail by force. It prevails by speaking English, overwhelms by its successes and its mental model. There is another threat to the global alternative: the civilizations that are far ahead in prosperity and standard of living underestimate the rest of the World with its coalitional potential. And the latter might initiate a global repartition. A global repartition of the 21st Century is not impossible!

We want to take a certain place in the world. Getting renewed, we will also take a new place—but in what world: the world of the Persian Gulf, the world of Sarajevo? Everybody now is on the horns of the following dilemma: interference provokes temptation as somebody starts to control the World, while non-interference means taking the risk of a new Munich Agreement. The principle of limited sovereignty as applied in Czechoslovakia in 1968 was once called “Brezhnev’s doctrine”. Now there is a tendency towards the World of limited sovereignties—but not in Brezhnev’s but in the American understanding of it.

And that’s what they call the new world order? We should adopt a realistic view of the ageing European society, of the young densely-populated continents that haven’t had their decisive say but are desperate to have it.

It is clear that the Cold War is not over. A certain version of it has ended—and we have entered its new phase.

Who has proved that man will manage to survive? “Not from zero, but from the beginning”

We have suddenly come to the fundamental question of our planet. Who has promised that man will manage to survive? Who can prove by facts that man can survive? It is true that Russia has been protected by its vast space so far. The methods of the Persian Gulf war can’t be applied to us, but it means that they will find a new method. We are entering the new era when the world will be concentrated in somebody’s hands— and what does it have to do with international law? It’s a totally different existence: you are not allowed to do this or that! But they will have to invent a different procedure to deal with us: after all, Russia is not Iraq. Europe might manage to stop Yugoslavia by seizing it by the throat. But who will stop us?

The Russian world still needs to get into the World deeply, considering the alternative directions that the world processes might take, before defining its goals. The apostle said, “Not on the ruins, but from the ruins”. And I am saying: not from zero but from the beginning! I found this concept a long time ago, in my dissident years. Realizing where the World was going, I was preaching: not from zero but from the beginning!

After 1946 it was impossible to annul a sovereign state the military way. This idea was stigmatized by the victory over Hitler—an enemy of sovereignty. The Gulf War was a war for the sovereign Kuwait. The fundamental principle of the Crimea Conference is that a member of the UN cannot disappear. Kuwait was won back—but less than a year later the USSR, a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, ceased to exist.

Nowadays any sovereignty may be regarded as loot. Having lost the principle of sovereignty, the World has become a different place. And Russia has lost the stimulus to protect the World.

We agree on two points—but disagree further on. The talk about the “Weimar situation” is only essential for Russia while we are considering the fundamental dissimilarity of the worlds together with the similarity of several particular constituents. Otherwise this analogy is futile and banal. It seems to everybody that we will make some trick and escape all the dangers. But the danger is already awaiting us on both sides. There is the danger of the uncontrollable consequences of our actions—and the temptation for the USA to become the manager of the globe: we tempt them into it by our weakness. In Russia we all lack this imperative: the law of the lowest threat coming from ourselves.

As for the world of future wars, you are right. It is human life—who knows what is more important in it? Who can determine it? We aim to find the least dangerous modus operandi in the ganglion of the system. Don’t think it is too little. It is a lot nowadays. And secondly, being more creative, this method will open people’s eye to fundamentally different opportunities.

And what if we are too late? We can’t possibly take such a risk.

We are not masters of all the future spontaneous and hellish things. We don’t know where the magma will burst out, and even if we knew, we can’t stop it. When you get into a car accident, what happens in the first instant? They have simulated this situation in a laboratory—with sensors, the proper way. In the first millisecond all the systems of the body switch on—absolutely chaotically, at random! Your liver, eyes, spleen—all starts working, but then the main process starts: switching off the unnecessary. And your survival depends on how quickly this process goes. A disaster may come from any side, and Russia should aim to rely on the adaptation syndrome. But if we base the whole policy on one single system and it fails—we are done for. Evolutionary selection has found a wise method. It is not switching on the seemingly necessary, but switching off all the unnecessary.

Some voices demand that the state process should be given a “final solution”, and I demand that it should be given inner freedom, as I have no ambition to control the future and establish a timescale and deadlines for it. My method is good because at least it is less dangerous.

Let’s learn to switch off the unnecessary, so that the necessary could switch on by itself, when it is required.

On the other hand, there are various ways to achieve success. Here is the fable of our race to Berlin. Stalin made up his mind to recapture Berlin before the Allies, at any cost in casualties. But how could it be done? The General Staff and Zhukov had to get to the Oder, cutting off the retreating German units. So they took a decision: our troops (600,000 of which have been killed in Poland) would march straight to Berlin. At the same time two strategic tank armies were advancing on the right and left of the front—with strict orders not to open fire. The retreating Germans saw the tanks speeding through the clouds of dust to the same pontoon bridges over the Oder, but they took them for their allies as they were not firing! So the armada was moving on—and on—and on, got through—and cut off the bridges!

They arrived in time—but could have failed. Do you really know other ways to come in time?

We’ve got a nodal point. We are revolving around it, but we haven’t studied it throughly, though we have palpated it. The Cold War, its incomplete depletion and the generic breakdown in people: what is hidden in the depth?

And what is the generic breakdown?

For the first time man was living in a straitjacket on the global scale, in the name of the supreme manifestations of what was then called progress. It felt like he was returned to antiquity, to the zone of tabooing, where he once again cognized the Prohibition that this time wasn’t caused by the limited nature of the man’s first steps from the impending doom of his species to self-preservation. No, people came to it at the peak of their spiritual ascent, as the winners of the terrible Second World War.

But when the Cold War ended, did peace really come? Who is the winner?

There is no winner. The man can’t return from this state to the state before, to the progress without a straitjacket. He can only return to the original foundations of his species. Why? Man is a creature living on the Earth. The Earth, in my humble opinion, is a unique body in the Universe. A combination of conditions favourable for life in general—and especially for human life.

And here starts the breakdown. Man, being a getter, has used the Earth’s resources set by the planetary and cosmogonic evolution. He has turned from a doomed species into the creature that is using everything available on the Earth. Now his internal resources will become his main resources. He has to get into this mode as he is retreating from the historical epoch that shows a tendency towards extermination of his species and higher life forms on the Earth.

Is it possible to do it by just breaking free from old settings?

All centuries are involved in it. And I am returning to what had been before this breakdown: the man as a getter, shaped by the climate, landscape, other natural conditions. Here I introduce the notion of three human spaces.

First, the man as a getter couldn’t support the existence of all the creatures technically belonging to this species.

Second, he couldn’t overcome the hurdle of selective premature death.

Third, he couldn’t fully satisfy the individual opportunities within the framework of the species.

The distributive function is connected with this triple limitation of the gaining aeon of human vital activity and unites them. This function is realized in the forms of authority tending to exceed the boundaries of strictly economical reproduction so that it could shift the sphere of domination and—indirectly, at others’ expense—replenish the shortage.

Within this framework there is something that is not directly related to the reproduction of the species and free from the shortage I’ve mentioned. Something that can overcome the hurdle of premature death and, probably, of death in general. This sphere of human existence lies within what we call culture. In culture man is actually universal, actually sufficient and manifestly behaves as a creature deserving existence.

This reality exists in non-material form and, in addition to the geopolitical and economical spaces, it establishes the third—human—space, where the idea of humankind emerged and is being produced.

The idea of humankind has no foundations in people’s daily routine. It maintains a complex relationship—of challenging and protecting — with the daily life. But it tends to realisation, and in the forms of its realisation it intersects with authority, creating geopolitical spaces.

There is a second plane specific to the immediate human vital activity and culture. This sphere is history. It is the area of the idea of humankind that is progressing but never reaches realisation. Upon the whole, history may be presented as a realisation of the unfeasible project of humankind.

But the shift of the centre of gravity to the human resources causes a breakdown. Started at the western end of the geopolitical space, this breakdown has a gigantic unifying effect, smashing the differences in the structure of human civilisations, overpowering their connection with the primary factors of human life and culture. The so-called globalisation makes both the idea of humankind and culture as the spiritual routine of people redundant. But the varying dynamic of cultural existences was the indispensable condition of the species’ reproduction! The species can’t reproduce itself as it used to. It has technologically overcome a number of hurdles that it couldn’t clear before, but it has also eliminated something without which it wouldn’t have become the human species.

That’s where it got stuck. The redundancy of culture shows up: its perception has become the subject of reflection and creative work. In this new existence where the man has become a resource, geopolitical spaces seem unnecessary; the space of man himself has become redundant. At the same time the danger of the human species’ termination has increased: Homo may be levelled by the high, “clever” technologies of the progress. That is to say, Homo sapiens will have to protect himself from the achievements of his own activity, to seek a new basis and foundation for the varying dynamic of the humanity.

I don’t understand, are we now already on the other side of history? The second advent has happened?

When I say that the idea of humankind wasn’t realised, I don’t mean to sum up history. I mean that the idea that used to lure people with its unfeasibility, doesn’t provide sufficient reason for them to get inspired and act for its sake any more.

I haven’t said that the idea of humankind has been “played out”, neither do I believe that it was “discredited by communism”. I consider it among the original difficulties of the reproduction of the human species. The incongruous conditions make man a vitally dichotomous creature: local and planetary, tending to equality and to uniting under the banner of universalism—as well as to eliminating the distinction between kin and strangers.

Where is the focal point? It’s the fact that people are not driven by the idea that used to drive them by its unfeasibility. The grandest project that sometimes inspired people with its impossibility, and sometimes discredited itself by its loathsome embodiments, urging people to start anew. There is apparently no impulse for all that now.

At the same time, the shift of the centre of gravity to the man’s own resources implicitly creates a new unifying tendency. The latter wasn’t included in the conditions of reproduction, and it is mortally dangerous for man as a species, because the dynamic of variety is a condition of the species’ existence. The illusory end of the Cold War evoked murder—Homo sapiens turns to the primary premises of existence. In doing so he summons the forgotten spirits of those primary premises.

Russia is prone to it like no other place because the idea of humankind was performed here—by minds, images and lives!—on a compact temporal stage of only two centuries, which now becomes apparent in the banal dead ends of daily routine, in man’s weariness of miserable characters and bloody random circumstances flashing around.

It is not enough to introduce Russia as Europe’s frontier and the polygon of humankind: it has a prospective way out of the whole collision. This way out is to recreate the human space despite the fact that its original foundations in the idea of humankind are gone. The question is, what role will be played by what used to be called “culture” but has stopped actually being it, as it has been moved to the sphere of daily life.

Culture is being vulgarized, “dumbed down”—do you mean that?

The idea of humankind is leaving us, and culture suddenly becomes aware of its own redundancy! The former has stopped inspiring the unfeasible that encourages achievement despite the losses (the basic principles of all revolutions and the like), while the latter has stopped resisting history’s influence upon man. A battle for man is going on in the field where he has become the main resource. He contains the only resource of his species’ reproduction now, which is mortally dangerous.

There are some forestalling figures—Mandelstam in his Voronezh poems or Fellini who seems to be limited to Italy. But what is “being limited to Italy” for him? What is “being limited to Voronezh” for Mandelstam? We are talking about culture which is regaining control of daily life. Having acknowledged the priority of daily life, culture can enter it without losing itself— that’s what it aims at. It doesn’t even count on being fulfilled in the distant future!

But together with the idea of humankind, the notions of the past and the future are passing away too. If there is no idea, driving man with unfeasibility, there is no collision “past vs. future”. “A feasible future” is not the future—it is extrapolations that are beyond the notion of the future. As a result, the vacuum of politics of the future has emerged.

The politics of the future emerges when we say that the future is not like the present. It should be brighter, better; it will bring man what he lacks so desperately. That’s why man used to consider all the previous stages as a prologue to himself, who was dissatisfied with his present and was overcoming it for the sake of a better, brighter future! He was building up his whole existence as the genesis, the genealogy of humankind. Where will we get the future of the past without the idea of humankind? What ground will it grow on?

All right. But if there is not such a plan and man just exists? The day when he managed to achieve something is a good day, but some days are just wasted. Is there man as a getter, as a hedonist, as anybody—even as a crafty businessman?

And what if it is a Colas Breugnon—like the cabinet-maker I told you about, who found happiness in every item he made? He worshipped the god of daily life and it was all radiant for him! He needed nothing but the moments when he joined in history, or when history involved him. When my cabinet-maker went to the war and, having no shell in his rifle, advanced to Vitebsk with the Kalinin front to attack the rear of the Germans, he could easily end the war for himself—but didn’t! Unlike me, who had no military skills, he knew how to fight, but he wasn’t driven by anti-fascism. He didn’t want to fight at all: he was conscripted, drafted, even forced by history.

An idea foreign to cabinet-makers, I dare say.

The idea of humankind is inherently foreign to everyone! It is always directed from the outside inwards and will never take full hold of man’s insides. This idea is only adopted by those who can lead all—or many—people along this way. I wonder what virus it was that Ancient Judea transmitted and that has been spread on and on ever after?

All this complex, wild, bloody and saintly mass—all of it, I insist—is geneticized and included in the basic set of conditions of the species Homo sapiens’ reproduction. But this trick is about to end today. What will follow? Will it cause some damage to man? Where will we find a new source of resisting the unifying expansion of man that already plays the role of the main resource of the species Homo sapiens’ reproduction?

Or am I totally wrong, which is not impossible? I am too concerned about the fate of Russia and the idea of humankind.

If it is madness, there is a method to it anyway. But culture with its autonomy has become unemployed in your picture, it doesn’t fit in the general progress.

I won’t take flippant discussions on cultural topics. What is culture? We are returning to the old topic: if culture is our everything, do we need this word at all? When culture had to make its own redundancy a subject of reflection, it joined in the people’s fundamental collision. Culture is hostile to man as a getter who—in a certain place, at a certain moment—overcame the impending doom of his species. A memory of the impending doom and of man’s overcoming it is alive inside culture. When this memory is lost and is no longer intimate and vital for man, culture also becomes redundant.

But the very essence of the globalization myth is “now man can do everything”.

This “everything” is based on his ability to exterminate himself and life on the Earth—and here culture plays the role of a duellist: it challenges man, saying, “You wish! Not exactly everything!” It insists that man mustn’t be able to do everything. That’s the only way to open the gate to the World of the dynamic of the various.

The idea of humankind has turned from an unfeasible project driving man with its unfeasibility—into what? Has this idea been depleted? Or has it exhausted its resource of unfeasibility, like the Second Advent? No, it has been discredited by feasibility that has stopped coinciding with the utopia of the humankind and become its simulacra, its shape-shifter.

Berdyaev has warned us against the dangerous simplicity of realizing utopias in the 20th century.

Yes, he was driving at dystopia—but after Stalin even that wasn’t enough. What is worth researching? I have said that man is at risk of losing some of his decisive characteristics. But what are those characteristics that, being indispensable conditions of the species’ reproduction, may be lost while physically the species lasts? What are those frightening moments?

The unrealized humankind was seemingly realized by the globalization. The project of humankind as a condition of the Species’ reproduction has become impossible—while as globally realized in various forms, it has become a probable factor of self-destruction. This point is important for me.

So, history has been depleted, while Christianity that gave birth to it, lives?

Classical Christianity has evaded extinction by refusing to take part in history directly, while communism missed such an opportunity— and the situation of the Cold War finally eliminated this possibility. Then happened a secondary breakthrough, that can’t be reduced to its preconditions. This is a breakthrough from the sphere dominated by the Cold War and the most absurd prospect of total extermination of man and higher forms of life—to the vital activity of man where the main resource will be not the Earth but man himself.

In the 20th Century man returned to the co-ordination with the universe that was highly important for his archaic ancestor. Once again he felt himself a mortal creature belonging to a species. This feeling relates his co-ordination with the universe to current history. Man is concerned about the fate of the Universe within the boundaries of which he became a lonely figure.

This once again became a measure. Who cared in the 19th Century whether the Solar System would exist for a thousand or a billion years? Contemporary man has unconsciously taken death into account in his attitude to the entity and his place in the macrocosm.

Man is returning from the Socratic revolution to the pre-Socratic time. He doubts the categorical imperative of man being defined through humanity. The Nazi gas chambers and Kolyma Gulag camps make it impossible to declare that man is the measure of all things: it is the basic principle of life in a concentration camp anyway, without Socrates.

With the two characters—Hitler and Stalin — human life turned out to be redirected to death. In this light we can estimate the scale of the task to re-discover life that has still to find its language and its approach to daily routine.

I would call my perception of the 20th Century luminous horror. Horror is still horror—but it has an inner enlightening side not related to anything in particular. The catharsis of the century is the need to be with somebody, enhanced to transparent poignancy. To be in a twosome in this century means to be with everybody on the Earth. This catharsis was produced by the most terrifying places on the planet: the Warsaw ghetto, Treblinka, Kolyma! Somebody might object that it is a question of psychology or existence. But I insist that it is our essential attitude to history, not yet fully comprehended. When we say that nothing must be done bypassing man, it means he shouldn’t be prevented from being somewhere with somebody. All human life may be aimed at it. But before that it should become incredibly rich inside itself and learn to combine the human “separately” and “together”.

I am facing the moment that makes me think myself over, down to the very depth—though I know that nobody has ever managed to do it. Either what is going on is void of intellectual interest and I can consider it to be external to me. Or, the more banal the situation in the country is, the surer I am that there might be something frightful behind Yeltsin—something concerning the creature calling itself man, something that can’t be expressed with words. It’s hard for me to write when this feeling overpowers me.

Although, man is actually quite resilient. The existence of such figures as Yeltsin should be regarded as a manifestation of Homo sapiens’ inherent resilience as well.

Where do you see manifestations of resilience—in the absurdity of the Chechen War?

Look, while such people emerge and evoke some events, even detrimental, they are a test. They are gateways or holes to something that wouldn’t have happened without them. Man has some inner property that can be realised with the help of such characters.

Well, it could refer to anybody. Couldn’t it refer to Gorbachev?

No, it can’t refer to Gorbachev. Yeltsin has something different in stock for the World. There was Khrushchev, there was Brezhnev, but Yeltsin is not even a second Brezhnev—in some ways he is equal to Stalin. And Stalin’s existence proposed that something must happen to man. I have developed a new outlook: autocorrecting my view of the characters that I loathe but, much to my indignation, depend on. This man doesn’t appeal to us—he insults us by the very fact of his existence—but I autocorrect myself, correlating the absurdity of Yeltsin’s regime with the supposition that something must happen to man. This thesis is a little mystical, isn’t it?

You really puzzle me with the thesis of Stalin’s and Yeltsin’s functionality.

As for Stalin, it is my old thought. Let’s leave the easy path of chatting about good and evil and giving explanations for the fools—like, “Stalin won due to his insidiousness”. One might think that the politburo in his time consisted of trusting simpletons! What did he use to overpower those veterans?

The pathology of Russia’s history reveals itself through regular selection of such public figures. This pathology manifests in people and takes a grand and weird form where the personality, intellect and scale of the villain are all mixed up. Of course, Yeltsin has almost nothing to do with all this—but it’s high time we looked at some of his antics in the light of Stalin’s precedent.

I still don’t quite understand this chain, from Stalin to Yeltsin.

I think the emergence of such people is like geomagnetic disturbances warning us about uncontrollable large-scale avalanches and disasters. Their emergence means that in the nearest future something will happen to man—not additional to something previous, but different, large-scale, preceded by prologues and glimpses of foreshadows.

They say, if you take a realistic viewpoint things look simpler. From where I stand, no, they don’t. Otherwise everything would be so banal that you would fall out of the sphere of the intellectually meaningful. In which case, there is no point in being a historian. It’s better to escape modern life and research, for instance, the companions of Peter the Great: Alexander Menshikov on his own is a more colourful character than anybody I have ever met in the Kremlin!

It’s high time we dealt with some issues. Take Nicholas I. Before the interregnum of 1825 he was only notable for his enthusiasm for parades—but on December 14 he proved to be an extraordinary man. His first years after the executions of 1826 were marked by his attempts to change something in Russia—to be not only a hangman for the Decembrists but also an executor of their will. Take his impressive system of total control, punishing the bad landowners, his endless inspections—the odious system that he built up on the ruins of the Decembrist revolt and supported with his authority in Europe. But after 1848 he is a different man, who is impossible to convince with facts. At the peak of his power he goes down and takes everybody with him. That’s what Yeltsin will do with the help of well-bred fools.

And Yeltsin will be succeeded by “It”?

Yes, according to Saltykov-Shchedrin, by “It”.

I still don’t quite understand your concept of “villainous people”: what is their use?

Dear me, and what is our use?

It is not really an answer.

After Gorbachev’s abdication Yeltsin was undermined by the problem of making the second step on the same scale. He had no resources for a second start, so the problem of the second step appeared when the first one was already in the past. Hence the insignificance of the new regime that is trying to substitute the lack of content with whatever comes its way. The authorities attribute everything that is being done to Yeltsin. The insignificance of the authority is a frightful but potentially large-scale issue. Do you remember what Yeltsin and Gaidar’s team agreed on? They gave him some content relevant to the extreme ambitiousness of the authoritarian power. And this content was also pretended! It created an atmosphere of fervour in which what was going on looked seemingly irrevocable—while the problem of establishing a foundation for the second step was still there. If I started to explain such things to Yeltsin he would call us mental cases. Still Yeltsin knew what he meant when, talking to Gaidar, he hinted that the President was not the only initiator of the October murders.

Yes, it was important for Yeltsin. Was it something personal?

It was something personal but it was based on the whole system of ruling and governing. If you want to be an autocrat who can command events, you build up the system of command accordingly—which reminds me of Nicholas I. By the way, Stalin did not pretend that it was somebody else acting, rather than him. Even when he invented enemies, he did it in his own particular way. He took his own deeds and transferred them to the indictments—with additions. Why did he want even the NKVD officers to be linked to an imaginary “fascist plot”? If they were supposed to be involved in this plot there was nothing in the USSR that wouldn’t have been affected by it. Nothing! Why did he need it, I wonder?

The tactics are clear—it is not clear, what it was used for.

In his case it became clear only in retrospect—don’t you agree? If the finale should be taken as a definitive point, with Nicholas’ death—or suicide—the system collapsed. Stalin dies — and where is his magical power over lives? Neither the Politburo nor any other institution had any power in 1953. There was only his terrifying power: while he existed they didn’t have any freedom at all.

I remember my feelings—my impressions of Churchill’s speech published on the front page of Pravda: “a man who created the greatest empire” died! Mao Zedong’s famous obituary: turn grief into power!

And changes started to occur—wave after wave. One of the first things those people did after rising to power was cancellation of the night watch at work: in Stalin’s time it lasted till 4am. Now the working day ended at 6pm. And soon came the first rumours of something negative, terrible connected with Stalin.

And how does our President fit in this chain?

Imagine he dies tomorrow. What will happen next? We will have to start anew, with all the irrevocable things we have accumulated in every field.

Yeltsin thrived on the deficit of authorship that has been perceptible since 1980s. An avalanche of events—and triviality, pettiness, deficit of personality. Gorbachev wasn’t the author of what we were experiencing—and the contributors of the “Ogonyok” magazine even less so.

No, he wasn’t the author. Gorbachev was a cunctator and a deserter from responsibility. But we should do him justice, he had a hypothesis: if only he starts intensive activity in one narrow sector that, as he has been told, is limited and safe, everything will move on. But it did not happen.

Yeltsin combines deficit of authorship with the ambition to hold the ultimate copyright. It seems to people that there should be the author of all this nonsense somewhere—and he is so very persistent in claiming the authorship! This is a question that arises in our situation of destabilization that fails to turn into transition. In the epoch of Lenin and Trotsky the question of authorship was ridiculous: everybody knew that the authors were the party chiefs. On the other hand, they had no reason to claim the authorship: they lived under the impression that the Revolution was bigger than any of them. Sometimes I don’t dare say that the people who initiated apparently the most appalling mass murder in the 20th Century, were indicated to the World. It means that the mass murder was also indicated to the world, and I am not afraid of discussing this question.

What do you mean by “indicated”?

The world needed them, and they were indicated to the World. It was not predestined, but indicated. The World failed to do something without them—tried but failed. The citizens of Rome also wanted something, but failed—therefore others came, from the Apostle Paul. People wanted to do something intolerable in this century, that’s why they couldn’t do without concentration camps—hence the graves without names on them and deaths without graves. It means that even graves were indicated to us. I am ready to discuss this appalling thesis.

But how can we discuss graves?

I’ll start with the statement: murder is indicated to man. Hence the graves, and the graves of my nearest and dearest among them. And now I will explain myself. I won’t beat about the bush. I am tired, my life will end soon, I don’t want to delay it. I am ready to discuss it aloud.

I still don’t see the transition from the valuable thesis about bushes to the thesis about mass-murders being indicated to the humankind.

It is inside the type of thinking developed by the people who have survived the Cold War but have never left it, and now are clinging on to the possibility of the destruction of the world. Such people, even if they mean good and want to avoid deaths, still proceed from the assumption that extermination of humankind is politically possible. Especially in the present situation where everybody is condemning totalitarianism in word, but would never lose hold of the means of total destruction. I want to explore the origins of all that.

How did it happen that the century that has seemingly abolished the slavish pre-determination of human existence, has chased itself into the trap of collective suicide? I want to understand it. Lenin wouldn’t understand me, but I hope to understand him. I had to take the path of double reflection, telling about myself maintaining certain relations with Lenin while those relations have also evolved. He is a man who took a place in my life and has settled there.

You are speaking about Lenin, but he was not the only initiator of mass-murder.

Precisely. Next we need to stick to the point, unfolding the thought. I can’t facilitate or simplify the situation of the question for myself by renouncing Lenin, by saying that “the villains came and spoilt everything”. I could keep saying: “deviated”, “spoilt”, “distorted”, but I don’t want to. Lenin gave us an opportunity to do it — not only by creating the party and a political doctrine that didn’t have a subject...

Well, today you have chosen to be merciless to everybody.

All right, let’s speak about something amusing—cinema, for example. Ah, those post-war “trophy” films! My God, how delighted we were to see The Woman of My Dreams—feeling a light trembling at the shaken foundations of our views of life and the daily life itself: look how normal people live. Those people felt satisfied if nobody hurt them, they didn’t think about the World, and were contented even when they were dealing with some minor domestic troubles –like a drunkard of a husband or something like that.

We were different people, Soviet citizens. We had the spirit of dissatisfaction inside, the Russian spirit of change. There is a partition between the two breeds of Russians—and they have difficulty communicating. Sometimes they crossbreed into a nation—but immediately get apart again. And I no longer believe that the Russian human “bipartisan” system will be preserved.

After all, the Soviet predominance was indissolubly connected with the assumption that the World may be explored, understood and made comfortable following a certain model. Even during the campaign against “cosmopolitanism”, the Soviet was also global and connected with the World. And what if there is no pathway to the united World—as I see it now? I don’t think that Russians will be able to live the way people live in the West: “independently-communally”. It won’t work here as it can’t work in principle.

It means that the threat of collision is imminent. It means that something will happen to man again. Maybe it is not the last time, but maybe this time Homo sapiens won’t manage to get himself out of trouble.

Questions by Gleb Pavlovsky

Translated by Arina Volgina

Fragments from the book: Гефтер, Михаил.

Третьего тысячелетия не будет : русская история игры с человечеством. Москва: Европа, 2015