Reģistrējieties, lai lasītu žurnāla digitālo versiju, kā arī redzētu savu abonēšanas periodu un ērti abonētu Rīgas Laiku tiešsaistē.

Couldn't link to Twitter. Please try again!

I first encountered Donald Hall in the winter of 1968 when he came to my high school in Michigan to read and talk about his poetry. It was a big occasion for many of us more ‘literary types’. Poetry readings were not common in those days, and poets were an exotic species.

I remember Hall was clean-shaven and wearing a tweed jacket with elbow patches. He would have been just 40 years old. He read a poem in which he described a urinal weeping, which many of us thought was very effective.

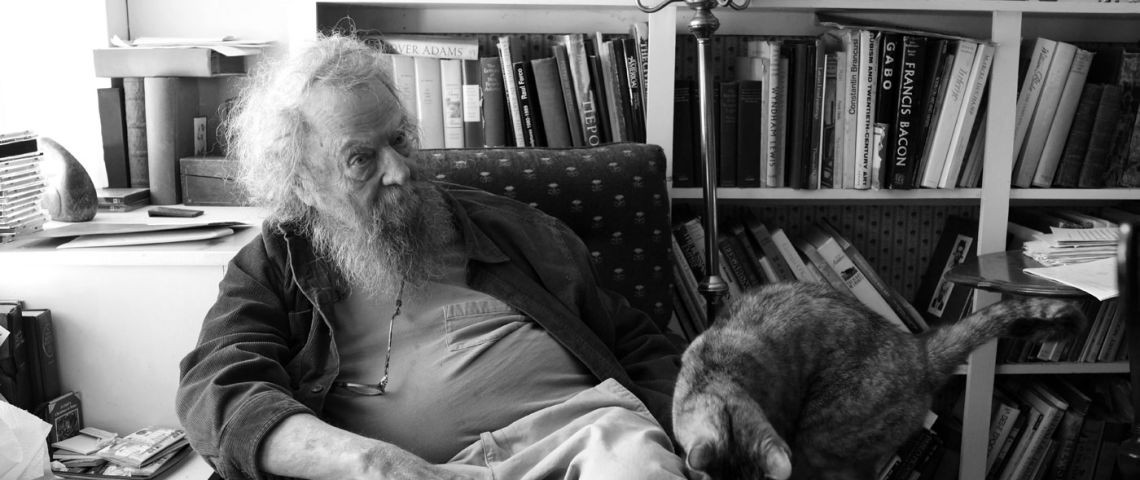

Four years later, I audited Hall’s popular course on James Joyce’s Ulysses at the University of Michigan, where he taught and served as poet in residence. By that time, the 60s counterculture had come and not yet gone. Hall sported a great wild beard and delivered his lectures with sonorous bardic enthusiasm. He was a major campus figure, still a few years from giving up academia to live in his grandparents’ home in New Hampshire—he would move there with his former student, poet Jane Kenyon—and forcing himself to become an industrious freelance man of letters as well as poet.

It’s Hall’s status as one of the last of that species—the freelance man of letters—that now claims our attention, alongside his many published books of poetry. At various times, he has served as editor of the influential New Poets of England and America, interviewer of T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, among others, and biographer of Henry Moore, written essays and memoirs, including the immensely popular String too Short to be Saved, edited the textbook Writing Well and authored various children’s books, including the now classic Ox-Cart Man. My hand tires before reaching the list of Hall’s many honours and awards, though I must note that he served as America’s Poet Laureate in 2006 and received the National Medal of Arts from President Obama in 2010.

Hall is a member of the generation of poets that includes Galway Kinnell, Robert Bly, Adrienne Rich, John Ashbery and Philip Levine. He knew many of them and is fond of telling stories, especially about Bly—the two have had an affectionately rivalrous friendship since they were at Harvard together in the late 1940s.

Hall’s own poetry is free-spoken and rich. It draws extensively on the New England places of his boyhood, and in recent years on his relationship with Jane Kenyon, then on grieving her untimely death. He often speaks about the long work of building a poem through drafts, proudly owning that a good many of his have undergone more than a hundred successive drafts. Structural and tonal integrity are all-important. Several years ago, Hall announced that he was no longer writing poems—that poetry required ‘testosterone’—and has since confined himself to prose, often to essays about aging.

I got to know Hall in the early 1990s when he invited me to co-edit Writing Well. It was a signal honour, as this was the textbook my own teachers had used in English classes in high school. Our collaboration involved a good deal of correspondence, much of it laced with Hall’s wry humour. He would let himself get bombastically outraged about a badly used semicolon, but there was always the sense that his reaction was for fun, as much about theatre as his concern for usage.

For the last 20 years, Hall has also been a yearly visitor to the Bennington Writing Seminars, where I’ve taught and which I now also direct. His summer visits have acted as markers of continuity, and I can flash forward from his very first visit when he came with Jane Kenyon, to later years when he read his poems of grief, to more recent summers when he has anecdotalized with great charm about his meetings with Frost, Pound, Eliot… He particularly relishes his story about Eliot, how when he was a young Harvard student spending a year at Oxford, he met the poet to interview him. As he was leaving, he asked Eliot if he had any advice for a young aspiring poet coming to England for a year. Eliot—the ‘Ol’ Possum’—gave thought and let the silence build for a time. Finally he looked Hall in the eye, and without cracking a smile said, ‘Warm socks. Be sure you bring warm socks.’

Sven Birkerts

I tell you, the first time I heard Brodsky reading his poems—he was magnificent, powerful. And then I read the first translations of him in English, and I felt like an idiot. They had a rhyme and everything, but the translator just used a terrible language. So embarrassing! He was so wonderful up there…

Could you understand his English?

No, he was reading in Russian. I was reading translations—terrible translations! I had a lunch with him with the people who brought him over, and I remember he was saying: “Yevtushenko is shit! Voznesensky is shit!” In English, but very loud. I never knew him well. He left and went to New York very soon.

But then he worked at the same place where you did?

Yeah, for a year or so. Then he settled in New York… And he was a smoker. Toward the end of his short life he said: “I am dying for a smoke” or: “I am dying for a cigarette”, or something… Thank you for your magazines!

There’s Brodsky on the cover, by the way.

Oh, is it? There he is smoking, ha-ha!

Why do you smoke?

Why? I have the habit. Why do you smoke?

I like it.

I like it too, of course.

Why do Americans not smoke?

Health—the propaganda about health. They’re all afraid to die. And then they find smoking disgusting. I walk around with a cigarette and I see a stranger go like that…

Recently the Minister of Health of the Czech Republic said that freedom is more important than health. The Czech Republic is the last bastion in Europe where you can smoke everywhere.

I went to Prague ten years ago and I smoked everywhere—in my room…

So freedom is more important than health?

Apparently for me. But I am almost 85, I am not worrying about it anymore. You know, I am not defending smoking particularly but I acknowledge it in the midst of a country that is fanatical about being against it. I have a friend who smokes—she does the dishes and cleans the house for me. We smoke cigarettes and talk about death.

Are you still writing?

I’m writing every day but I am writing prose. I wrote poetry for many years but it stopped and went away, the inspiration for it. Then I took up prose and… Out The Window—that was the first thing that showed me what I wanted to do. So I’ve been doing it every day.

That’s the place where you usually sit?

Yes, I can see the birds coming, and the barn. I love to look at the barn. Just when you were coming I was going to have a cigarette—the longing was overflowing me. Hey, if you want to smoke just bring an ashtray…

In your book on George Moore, The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor, you said to him: “Mr Moore, you are old enough to know the secret of life. Can you tell us what the secret of life is?” What’s your own answer to this same question?

The purpose of life, or the secret to life, is that you should have an ambition that overwhelms your life and that takes your heart and life in its hands. And the thing that’s totally important about the ambition is that you cannot possibly achieve it. And he [Henry Moore] talked about being better than Donatello or better than Michelangelo, and every morning he woke up desiring that, and every night he went to bed—“not today, not yet, I haven’t done that”. Over there on that little table there is a Henry Moore sculpture. He gave it to me! I wrote a New Yorker profile of him, and then I went back and saw him later and asked him that question. It’s a naïve kind of question—the secret of life—but he was a straightforward Yorkshireman, he wouldn’t feel ironic about it at all.

But that was Moore’s answer. What’s your own answer?

I think that’s a wonderful answer! The activity of writing has filled my life. My life was… I was twelve when I started. When I was fourteen years old I decided that this is what I wanted to do my whole life. And I have! I still am. It was poetry first, although I always wrote prose. And now there’s inspiration, the given of a poem, when you have words come toward you, and they please you and they sound good, they taste good but… you don’t know what they’re about. But you start from that. And the ones that you began with are likely to be the best lines of the poem. That used to happen for me every few months, with several poems at the start and then I would work on them. It’s stopped happening. It is probably linked to sex. When you get old your testosterone diminishes—it’s probably the reason for the decline of inspiration. But I still write prose and I enjoy it enormously. I don’t like first drafts, they’re no good, but I like revising. A lot of what I do has to do with the rhythm of the paragraph and the organization of sentences. I have something to say that begins me going but my desire in writing it is to make something that is beautiful.

Together with Sven Birkerts you have written a book about good writing.

Yes, Writing Well.

Is it possible to teach someone, or to learn, how to write well?

You can teach not to do certain things. You can teach about metaphor, simile and grammar, God knows. Writing Well—I wrote that some forty years ago so I am a little distant from it but I’m actually very grateful to it because it allowed me to give up teaching and to come here and write full time—make my living by writing. I’ve done that for 38 years or something. I’m not making a living now but I make some money. Poetry readings make money for a poet in this country. I did one on Monday for five thousand dollars but… it exhausted me. It didn’t use to exhaust me but it does now.

By the way, what do you think of Philip Roth’s announcement that he is done with writing?

Well, at about the same age I stopped writing poetry, which is the most important thing to me. I saw him… Oh, do you see that picture? We got gold medals from Obama. (Laughs.)

When was it?

That was 2011. Phil Roth was there too. He looked at me and said: “I haven’t seen you for fifty years.” I said: “Almost sixty.” I was in a wheelchair and he said: “How are you?” And I said: “I’m still writing.” And he said: “What else is there?” He obviously had the same feeling of his own work going poor and decided to stop it at that point. That was me with poetry.

But you said that after the death of Jane writing poetry was the only way to live.

Jane and I felt that way, yeah. But you get old, you get tired easily… But what are you gonna do? There’s no wailing or self-pity—you just can’t. You get old! I used to work writing ten hours a day—not always but frequently—but now I can only work one hour. Thank God I can work one hour!

How long did it take you to write Out The Window?

I started it in January 2010 and I was still making changes in August. An old story in the middle of it about the museum guard talking baby talk to me—that was so important! That happened to me in May of 2011 when I was going down there to meet Obama. And I came back and was able to write it into the sheet. A poem or an essay that’s any good has to have a kind of counter-movement. Most of that essay was a pleasure—I mean, a pleasure in looking out the window—and you needed to have something that moves against it. I thought it was funny that the guard said: “Did we have a nice din-din?” But of course that was another side of being old. And when I got that it made the essay come together. The last thing I remember writing for it—I was looking out the window and I saw a wild turkey mother and her three babies walking up the hill. And I remember writing that in. It was great fun to write!

I was recently in the hospital. You know that feeling when they are taking away your personality first, your sexuality second and then they are looking at you as an object of treatment—just an object that has nothing to do with me? Do you feel yourself as being someone from another galaxy in that sense?

Ah… I am totally conscious of the difference of old age but it’s been so gradual that I haven’t lost the sense of my identity. I’m sitting in the same chair that I’ve sat in since 1975. I’m able to go to the bathroom and cook for myself but basically I live my life sitting in two chairs. It’s a kind of a symbol of the limitation. There’s an upstairs—I don’t go there anymore—and there’s downstairs with a cellar—I don’t go down there anymore either… But it’s come gradually! So I’m still the same person, I haven’t yet lost my mind. I don’t think I will actually—my mother lived to be ninety and she was sharp. Nobody knows how long they’ll live but I don’t worry about the Alzheimer’s. Some of my old poet friends are going Alzheimer’s—their minds are going. Two of them in particular are going in and out, back and forth. I haven’t done that yet. So when these men are in the world, not out of it, I take it they feel like themselves. One of them telephoned in December and I asked him how he was and he said: “Sometimes I don’t know who I am or where I am. But then I come back. Some time I won’t come back.”

Is there anything beautiful in old age?

Oh… I thought that in Out The Window I talked about the beauty of sorts of being able to look out the window and enjoy it without having to do anything about it. But it used to be… 35 years ago we had no central heating so I would carry wood to the stove and then I would sit down and work. Then I would carry more wood to the stove and then I would sit down and work again. And I loved it! But now I can sit here and look out the window and love it. It’s good fortune—to be able to. (Laughs.) If you spend your time being sorry for yourself—it is misery! It is temperament I suppose. It isn’t that you can will yourself to accept limitation. But if you don’t accept limitation, the frustration will take over your life. When I was working ten-twelve hours a day, I told myself I was doing it because of Jane. Jane was nineteen years younger than me and we knew that she would be a widow for a long time, and I wanted to leave her enough money so that she didn’t have to do torturous work or something, so that she could write poems all the time. I wrote for magazines every day all day. But although I told myself that I did it for Jane, which was true, I was also doing it because I loved it. I had the freedom to do it and also a sort of conviction of necessity. Two years before Jane died I was supposed to die—I had half of my liver taken out. I had cancer in my colon and it metastasized into liver. The surgeon told me: “Of men your age who have this disease thirty percent are alive after five years.” I was about 65 when that happened. Jane massaged me and she was trying to run the cancer out but we both knew that I would die soon. And then one day Jane said: “I think I am coming down with something.” Like you would say when you had cold coming on, only it was leukaemia. And then it was fifteen months and she died. So she died instead of me, which is so strange! The irony still overcomes me. I should’ve died, she should’ve lived. I’ve written so much about her death… For five years after she died I don’t think I wrote about anything else. I wrote poems about her and prose too but the poems Without are probably the best thing I’ve done in poetry. After she died I hated the money I had saved, because I had saved it for her. There were nine people—my two children and their husbands and wives and five grandchildren—and I gave them each a sum a year for many years.

You said that after Jane’s death you wrote perhaps some of your best poems. I have always wondered how a poet can evaluate his own poems.

You don’t know! You really don’t know whether they’re any good—but you write anyway. I always worked on poems first thing in the day. Jane was slower to wake up. And some mornings I would come out of my study and say to her: “I am amazingly great!” And other mornings I would come out and say: “I am pure shit!” She just laughed. She knows why I am feeling this way or that way. But there is no knowledge—knowledge that anything you write is good. In my interview with Eliot I said to him: “Do you know you’re any good?” And he said: “Heavens, no! Nobody who’s any good knows if he is any good.” (Laughs.) It’s a little stiffer in the interview, he wanted to change it but I was so glad he said that.

To me that conversation sounded pretty stiff, unlike the one with Ezra Pound.

Eliot spoke in paragraphs. You know, in England members of parliament stand up and talk in perfectly correct and clever prose but it sounds exactly the same from person to person. It’s totally correct and it addresses the issues but it’s stiff! Eliot was American but he learned to speak like an Englishman. In the Pound interview I would ask him a question one day, he would answer half of it and he would answer the other half of it two days later. But Eliot read the transcript and he made very few changes—it was all there!

But if it’s so difficult to evaluate your own poetry, is it easier to evaluate another’s?

I’ve always felt so but when I was younger my opinions were stronger and more confident. When I was 25 I knew who was good and who was bad, and now—not so sure. Every poet that I’ve known to get old has felt his judgment becoming less certain. In my own work I believe I’m pretty good at knowing what is better than other things—you know, to cross out a line and write a new one—and it’s better. But whether the whole poem is as good as I want it to be… I don’t know for certain. When I was young I thought—oh, if I get published that means I’m good; if I win a prize, I’m good. But, you know, it doesn’t mean anything. Every medal—this is common—every medal is a rubber medal. There’s this gold medal that Obama gave me, there’s the Pulitzer, the Nobel—they are all made of rubber, meaning that they’re not real, those things. Getting a Nobel does not mean you’re great. Seamus Heaney is a wonderful poet but Pearl Buck won the Nobel. And John Steinbeck, who is better than Pearl Buck, is not good enough to have a Nobel but he has a Nobel.

May I ask you about Robert Frost? Brodsky thought him to be a terrifying poet. Do you agree?

I agree absolutely. And he did not want people to feel that about himself. Lionel Trilling gave a speech in which he talked about suicide, about the longing for oblivion that is in Frost… I met him when I was sixteen and at some point, I don’t know when, I discovered the terror. One of my favourite poems, seldom mentioned by people, is To Earthward. Do you know that one? It’s terrifying! Love at the lips was touch / As sweet as I could bear… And now he feels—I don’t know how old he was when he wrote it—that he cannot achieve that feeling anymore. At the end he says he longs for weight and strength / To feel the earth as rough / To all my length. Ok, he’s talking about lying on the ground but he is also talking about being under the ground. Even in the famous one, which is a kind of a cliché, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening—even here there is the thought of oblivion and maybe the pleasures of oblivion. Not suffering anymore, no more frustrations…

There’s a lot of trees as well, and if I’m not wrong Robert Frost was afraid of trees. At least Brodsky wrote something to that effect. The tree for him was a separate being—like I am here and the tree is here, as strong as me or even stronger, and there are two realities: mine and the tree’s. Are you afraid of the nature of trees or are you afraid of anything at all?

Am I? (Silence.) I don’t feel that fear, no. I tell myself that I am not afraid of death, and when you insist a lot on one thing it means that you feel the opposite. My father died when he had just turned 52, my wife died when she was 47, and I endure. I watched her die, and I watched my grandmother die. I held a hand of people turning cold—I feel close to death, other people’s death, but of course that makes me feel that myself too. I cannot identify fear of the natural world, I cannot think of that, but in Frost I wonder if he projected his desire and fear of oblivion into the tree. I don’t know. You make me think! (Laughs.)

In the literary anecdotes which you compiled almost all those about Frost speak about his envy.

Such a childish thing! Talking about the cause, one of the things was that it took him so long… He was almost 40 before anybody recognized him as a poet! You probably know that he sent poems to The Atlantic and they would reject them. And he went to England, published two books… Ezra Pound helped make him famous back here. The Atlantic asked him for poems and he sent them the same poems they had rejected and—hah, they published all of them! Frost and I, we were walking through the hallway of classrooms at the University of Michigan—he had been there even before I was born. And I was walking with him and I said: “Oh, I teach them, Rob”, and he said: “They didn’t make me teach.” (Laughs) He always said: “There’s only room for one at the top of the mountain.” He was pissed that Eliot was at the top of the mountain! I don’t mean that Eliot was really better but the “top of the mountain” was composed of articles, praise, prizes like the Nobel… You know why Frost was never considered for the Nobel? Because he looked like a regional poet. But he was a universal poet, he wasn’t regional—he used New England. He was insanely intelligent but he was vain. I played softball with him one time when I was sixteen, with a bunch of people. His team had to win and he would bend the rules! He had to win, all the time!

He used New England you said…

He was deeply, intensely in it—that was his scene all the time.

And why do you yourself live in the countryside and not, say, in New York?

In my childhood I lived in the suburbs of New Haven, Connecticut. There were six-room houses, next to each other. The people who lived in them had the same income and drove the same cars and so on—it was all the same… I came up here every summer—this was my great-grandfather’s house and my grandparents’ house.

It means somewhere from the mid-19th century?

My great-grandfather was born in 1826 but he bought this house in 1865. He lived a long life, he died in 1914, well before I was born. But every summer I came up here. And my grandfather and grandmother lived here. Sometimes they made five dollars a month but, you know, they’d grow a pig and they’d slaughter it and hang it up in the shed and carve from it. And they had a huge vegetable garden and my grandmother boiled them and put them in jars—maybe five hundred jars of beans and corn and peas… Both my grandmother and my grandfather worked ten or twelve hours a day. This was her empire—the house. And that was his. But they were equal! Because they both had a domain where they were chiefs. They never thought they were poor—it just wasn’t a cash economy. And when my great-grandfather was alive the farms were prosperous, and he had maybe two horses and oxen, but there was an agricultural depression in America, before the Great Depression of 1929. So gradually the farmers got poor. They never had bank accounts or money—they had land, land was what people valued. Oh, and for food… Sweet came from honeybees up there and from maple sugar back there, and one year my grandfather and my great-grandfather together made five hundred gallons of maple syrup and they sold it for a dollar a gallon. They got five hundred dollars. What do you do with that? You buy a hundred acres of land!

But what about you? Why do you live here?

I loved this place where my grandmother was born in the room in there and my mother was born in the same room. And I loved haying with my grandfather. He had a horse-drawn mowing machine but at the edges of the hayfield you’d have to scythe it. The mountain up there was pasture and he kept about seven to eight Holsteins. He milked them twice a day. Holsteins are big milkers but not so much cream. My last cousin who farmed couldn’t get a hired hand and he sold them at an auction. He had fifteen registered pure-bred Holsteins and he sold them at an auction—the Japanese bought all of them.

My grandfather was a great storyteller. He memorized poems—bad poems—but he would recite poems to me all the time and tell me stories. He had an enormous fund of stories, and of course it was a storytelling place. In Connecticut people listened to the radio and had beach parties and so on but up here people met and told each other stories. Occasionally it’d be made up or a joke but often it was about a fellow who lived around here and did this and that. Often you’d laugh, occasionally maybe you’d cry or feel sad but I loved listening to the stories.

I loved my grandfather more than anyone, except Jane, in the world and I love this place therefore—this house, this farm, this barn, everything. When I was fourteen years old I planned to live as a sort of hermit upon the mountain and write poems and make my living by trapping foxes, mink… I thought I would live here and I would write poems but I would make my living by writing a novel now and then. (Laughs.) And then I knew I would never live here. And some of the poems I’ve written are about never again being able to live here. I believed it, totally! And then Jane, who was from Michigan, came here on visits and she adored it! So Jane and I, we moved and lived here. I was somewhat afraid of the move, but she wasn’t afraid of anything. We came here thinking we were coming for one year and after a month or so Jane said that she would chain herself into the root cellar rather than go back. I loved the idea! I was freelancing, and when you’re freelancing—how are you gonna buy the groceries? After a few years, two or three years, I stopped being worried because something always turned up and I worked all day.

What’s the secret to your wonderful relationship with Jane?

Jane, when I first met her, was 22 years old and I was 41 years old or something. She was writing poems—one or two of them were really good, and they got better. She lived with a guy and I heard they were breaking up, and I liked her a lot so I asked her out to dinner. This was in the ‘60s, and if you asked a girl to dinner it meant you’d have breakfast too. Then it happened every two weeks, every week, every two days… We kept getting fonder and fonder of each other. But we thought we couldn’t get married because she would be a widow for so long—19 years’ difference. Thank god we did! Her first book came out when my fifth book came out. We lived here, and she just got better and better. So her life, from, say, 25 until she died was an increasing scale of excellence and also of recognition. I remember the day the New Yorker bought her first poem and it published a lot of her. And a curious thing—when I married her, her face was not pretty. She had a beautiful body, always, but she wore straight hair to here and she wore thick glasses. And she got wonderful bones—her nose, her cheekbones… And she got prettier and prettier and prettier. She grew her hair out and then she got lenses for her eyes and her face and bone structure just sprang out! So that at 45 she was really beautiful and much more so than when she was 35 or 25. It is as if the growing excellence of the poems permitted her to be beautiful. Have you seen pictures of her? Anyway, because she got so good it helped me. I sort of led her, I was her teacher at the beginning and by the end of it she was ahead of me, she’d pull me by. But it was a great thing for my… I published a book in 1978, three years after we moved in here. Almost everybody who talks about my work thinks that it began then although I had been writing and publishing for many years. And I think it’s probably true. It was her presence and the poetic seriousness. And she adored living here! So we had that in common too.

Could you describe your routine day? How do you spend a day?

Well, now it’s very different from what it used to be because I get tired. I’m simply too exhausted—and I didn’t use to be. (Laughs.) Let me tell you about a day then! I would get up at 5 o’clock and I would put logs in the stove and I would open the draughts and pretty soon it would be warm in here. And I would drive out and get a copy of the newspaper and when I came back I would make coffee and I’d bring coffee in to Jane. She was slower to wake up. She would walk the dog to wake up and get to work. I would work on poems for one hour-two hours and then I would feel either that I was losing my touch or I would feel too excited and it would get in the way of working. So I would stop working on poems and I would work on a children’s book, a short story, an article for a magazine… I’d work on four or five projects during the day and often beside me there were different projects on the floor. I’d stop at page seven one day and the next day I’d pick it up and write page eight and put it down again. Many people have to work on one thing at a time but I thrived by working on many things at a time. Then we would meet and eat a sandwich or something and then we would lie down and take a 20 min nap, every day. I swear, it was just about 20 min every day! And then often afterwards we would fuck. We would wake up after 20 min nap and grab each other. I mean, this was our day, you know? When I got to be 65 or so I made it every other day. She would wake up in the morning and say: “It’s a fuck day!” She was very spiritual and she was ve-ery sexual. Then in the afternoon we would go back to work some and often after that I would read to her for about one hour. She liked to listen, I liked to read. We read poetry—Milton, Wordsworth—and we read the Bible and probably read Henry James more than anybody else. He is wonderful to read aloud! Then we would go back to work again to, say, four to six and then she’d make supper. I cooked for family dinners—I cooked when there was big quantity involved but she cooked for two people, which we mostly were. We would light candles in there and she’d bring in the supper—it was lovely. She often had a glass of wine while she was cooking; I might have sit here and have a beer. She went to sleep earlier than I did, she’d go to sleep at 9 and wake up and have coffee at 6 or something like that. But I would stay awake and read until 11 usually, lying in bed with her. That was our day. Now when I wake up I feel tired instead of feeling at the height, you know? I have a girlfriend, she is 57. She comes two or three days a week, two or three nights a week. I’ve known her for ten years… When Jane died at first I couldn’t stand the idea of settling with anybody. But I had to have women, and I went this crazy—I had women all the time! Then finally I got to the point where I couldn’t stand it for one moment. And I am glad we were together for about ten years—that’s really nice. We do everything now except fuck but we did do that, I have a memory of it.

You have some poems about Jane where you use not ‘I’ but ‘he’ and ‘she’. Do you sometimes think of yourself as about ‘him’?

I don’t think so. I know why I did that—I wrote it and worked on it with ‘I’. I was writing this book Without—I was aware that I had no judgment at all because my emotion was so deep as I wrote it. So I sent it to friends who would tell me the most help. And there was a woman who wrote to me and said—change ‘I’ to ‘he’. I did, and then I realised that it was like a hundred acres of bushes with pine trees sticking up now and then: palm trees, pine trees, whatever—the ‘I’ looking up. And it called attention… In this book there are passages about Jane—it called attention to me so I changed all the ‘I’s to ‘he’. For that section of the book I thought ‘he’ worked out better—not just visually but for taking a better look at a husband and wife, and the wife is dying with husband by her side. And without saying ‘I feel this way’, ‘I feel that way’—I felt it improved it. Another interesting thing to me is that at the end of it I wrote a whole lot of letters to her. I began at my desk and when I was writing those poem letters I felt happy! That was a year after her death or something. And there it was ‘you’. After I finished the book, about a year or two years after she died, I couldn’t say ‘you’ anymore—I had to say ‘Jane’ because she’d grown apart that much. I lost the ability to address her directly… Last Monday it was 18 years after Jane died. I did a reading that day down in Massachusetts and I read the title poem Without.

You said that you feel close to death. What does it mean—to feel close to death?

I have no pain—I can’t move my legs well but I have no pain at all. I am able to work a little bit every day. Actually Linda, my pal here, her life will be more disturbed than anybody else’s and I feel bad for her. When we were first together, one time we were in England and after making love she said: “I will lose you.” She didn’t mean we were gonna break up. And then a year or two ago I said to her: “What are you gonna do when I die?” And she said: “I will sit in your chair for two years.” She hasn’t had in her life anything like my Jane—great marriage is rare! I had 23 years with Jane—20 years in this house.

Do you have any idea why great marriages are rare?

I don’t know. I just see it all the time. I look around and I ask my friends and I can’t think of anybody who has as happy a marriage as Jane and I did… Many people continue to be married but don’t talk to each other anymore—they don’t connect anymore. They live together but they are separate. Jane and I had poetry together and then we also had something that held us together that would sound negative—and that is that of course we were competitive but we were very smart about not… If one of us felt grumpy, both Jane and I learned it’ll go away. We had one fight a year and therefore it was terrible. I mean, some marriages fight all day but we… We could send poems to a magazine and on the same day two of those would come back—one of us would have a magazine take the poem and the other would not, and the one who had been rejected couldn’t be quite so happy about it as the other one was. But I certainly watched her rise in publication, in general esteem and prizes and so on with unmixed joy. She also saw me win this and get that and she was joyous too. We weren’t competitive in the sense that success made us jealous of each other but… Oh, there’s a story! At the very beginning of our marriage some friends of mine would advise us to read aloud together, and of course the audience knew me and didn’t know her. And that would make her feel bad, and she said—we can’t read together anymore. I said, OK. Then, when she got to be better known, we would read separate from each other—I’d read one night and she’d read another night. And then one day there was a question time—people could come and ask us questions. And she got three times as many questions as I did, and she said—I think we can read together. So we did! And we’d obviously read A-B, A-B. And if you read A-B, B is the more important one. So we switched each time—one time I’d be A, one time she’d be A. One time, I remember, we were reading in India—and then we flew home and we had a reading right away—we were exhausted but we remembered who’d been A and who’d been B the day before! (Laughs.) But it was a kind of competitiveness that linked us, it didn’t put us apart.

I have a friend who is all the time dreaming of writing something—stories, articles… But the family needs money, so she is translating, translating and translating. Could you say something to her?

I can say a little something to her. Before I moved here, I was a teacher at a university for many years. I didn’t teach all day but I had to think about classes, correct papers… That was frustrating—that I couldn’t give the time to writing that I wanted. I solved my problem to a degree—I didn’t have at that time to write all day, and I couldn’t anyway, but I got up early. My temperament was that of a morning person. If I got up at 5 or 6 I could work for a couple of hours and I learned how to shut out the job. At 7 or 8, after two hours of doing my own work, suddenly the university would rush upon me—but I kept it away for two hours, it didn’t interrupt me while I was doing my work. Doing two hours a day of my own work kept me going and I was able to produce quite a bit. I have friends who are not morning people—two poets in particular—who have probably done their best work from midnight until 2am or something. When you are overwhelmed with working for a job—if you can work it somehow to set aside a particular chronological space where you may be able to do your own work—every day, seven days a week—and then make a living during the whole rest of the day… I don’t know if she can do that.

Which season do you prefer now here?

Well, my favourite season is probably the fall, when the maple leaves turn red. Have you seen it? It’s enormously beautiful! I used to love the winter, more than I do now. I liked the cold—I shovelled snow… There was a kind of isolation. I like isolation! I like solitude. Sometimes Marianne Moore contrasts solitude and loneliness and there are times I have moved into it [loneliness]. But when Linda is here and I have a woman to hug and so on… But mostly she is not here—she teaches, she has a house, she has children. Most of the time I am alone and love it. Winter was somehow more singular, less convivial—people didn’t drop in so much. I loved it. But autumn was always my favourite. And summer and its heat—it’s much better here than it is in Boston or New York. But spring in New Hampshire is unpleasant—and it is ugly. The snow gets dirty and so on. But it is brief—it was called Month’s Season a lot…

The first prose book I ever wrote was fifty years ago and it was called String Too Short To Be Saved, and it was about the summers at the farm—about my grandfather and grandmother and haying. First chapter was about chasing wild heifers—you know the word ‘heifer’? It’s a young cow, one-year-old cow, before they get impregnated and start giving milk. There were two of them and wild, and my grandfather and I searched for them. Then I wrote essays about this and that… There was one essay called The Blueberry Picking—about going up to the top of the mountain, not very high. At the very top there were a lot of stone ledges with cracks, and in the cracks there were low-bush blueberries. Nobody ever picked them—too hard to get to. My grandpa and I went up with huge pails—the kind of which are narrow and wider at the bottom. My grandpa often wore a sort of ox yoke and carried the pails. We went up and all day long we picked blueberries, came back and then my grandmother canned them. But when I was writing it I was in England! I was writing it partly out of distance. I was in England that year and as we came down from the mountain I found myself writing that my grandfather said: “I have something to show you.” We’d come to a kind of a flatter place and walk along it and I look down and there are the rails of a railway track. We walk along it and there in the woods there’s a locomotive and a coal-car—all red with rust. But I was making it up! The book was all true except for that. The New Yorker published that chapter, and I came to see my grandmother, who lived to be 97… I was living in Michigan most of the time. After I came back from England the New Yorker had just published Blueberry Picking. Down the road was a gas station and I almost ran out of gas and I stopped just to fill it and the guy came up holding the gas pipe: “Where is that damn train anyway?!” People had been looking for it and exploring for it. There were two guys in Denver who said they knew just where it was and they could take you to it—but not today. I loved that! (Laughs.)

Questions by Uldis Tīrons and Arnis Rītups